by Beth Castrodale

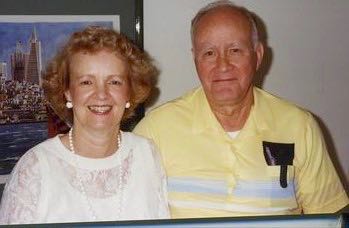

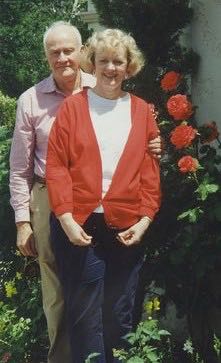

In late 2014 and early 2015,

both of my elderly parents died within four months.

Although their deaths were far from unexpected, I found myself unable to forge ahead on the novel I’d been working on over the previous two years. Against the loss of my parents, the novel felt trivial. Furthermore, grief diminished my ability to concentrate and to devote to the novel the close attention it required. So I set it aside.

Yet writing was, and still is, an important part of my life; in fact, when it’s going well I feel most fully alive. I wanted to give myself opportunities to re-experience that feeling, however fleetingly.

Thus, instead of allowing grief to get in the way of my writing, I let it become a subject of my writing, exploring loss through short works of fiction and nonfiction.

Over the months that followed, this strategy helped me cope with the emotions surrounding the deaths of my parents, allowing me to get back on track with my novel.

Writing About Difficult Life Events Helps Us Cope

Studies have found that writing about traumatic, stressful, or emotional events can improve physical and mental health. Compared with control subjects, those who wrote about difficult life events experienced such benefits as fewer stress-related visits to the doctor, improved mood, and a feeling of greater psychological well-being (Baikie and Wilhelm).

Studies also indicate that writing about dead friends or loved ones, in particular, is a way by which we can maintain a bond with them, helping us cope with their loss (Pennington).

Writing about loss can also allow us to make meaning—even art—from something we are struggling to come to terms with. As writer Tara DaPra eloquently observes in her essay “Writing Memoir and Writing for Therapy:”

“Perhaps the only recompense for tragedy—for death and loss of innocence—is the chance to create some measure of beauty. The marvel of a well-crafted sentence—finding just the right diction and syntax—is a small triumph over pain, a way to create order in the world.”

A dear friend of mine, poet Beth Gylys, described to me how important writing has been in helping her cope with loss:

“I likely became a writer in order to process grief. A sensitive, introspective child, I needed a mechanism to understand complication and difficulty. Though writing didn’t necessarily offer answers, it at least enabled me to tease out some of the messier dimensions of living: loss of life, ends of relationships, complicated love dynamics. When I feel writing percolate, often that urge stems from either a lack of understanding or a wish to wrangle meaning out of the inexplicable. Though my subjects aren’t always directly about grieving, an element of grief often compels me to write.”

Strategies for Writing About Loss and Grief

You might prefer to reflect on your loss privately in a journal, unrestrained by your internal editor or by concerns about what others might think of your writing. Or you might feel the need to express yourself publicly—for example, through a Facebook post or through a more formal piece of writing that you revise based on outside feedback.

Sometimes, you might use both approaches. For instance, after composing journal entries, you might eventually turn a critical eye to them, looking for larger points to make in a blog post or essay.

In the following sections, I’ll discuss both strategies, starting with the more private ones then moving toward public forms of expression.

1. Keeping a journal, but “directing” your entries.

Journaling can offer an opportunity to freely express emotions about loss, and it may provide a cathartic form of relief. Psychologists Wendy G. Lichtenthal and Robert A. Neimeyer have found, though, that for those who are struggling to make meaning from loss, directed journaling is more effective in helping them make sense of their emotions and experiences, and it can reduce symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress.

Lichtenthal and Neimeyer explain that, in contrast to open-ended journaling, directed journaling focuses on one or both of the following purposes: sense making and benefit finding.

Sense-making journaling involves answering such questions as, “How did you make sense of the death or loss at the time?” and “How do you interpret the loss now?”

In benefit-finding journaling, writers look for positive aspects of the loss, reflecting on questions like, “In your view, have you found any unsought gifts in grief?” and “What lessons about loving or living has this person or this loss taught you?”

According to Lichtenthal and Neimeyer, such reflective writing “can help us make sense of a world that doesn’t.”

2. Writing a letter to someone you lost.

When the absence of a loved one feels especially acute, or if you are feeling regrets about something you did or didn’t say to him or her, writing a letter can provide comfort and insight.

According to Neimeyer, “The most therapeutic letters appear to be those in which the griever speaks deeply from the heart about what is important as he or she attempts to reopen contact with the deceased, rather than seek ‘closure’ of the relationship.”

He offers several prompts as possible starting points for letters, among them: What I have always wanted to tell you is …, What I now realize is …, and The one question I have wanted to ask is ….

As Neimeyer and other researchers have noted, social media can offer a forum for sending messages to lost loved ones. For example, some people post their thoughts, feelings, and tributes to the Facebook pages of deceased friends or family members. Though these methods can be helpful too, letters allow for more in-depth reflection, in privacy.

One resource, AfterTalk.com, provides a kind of bridge between the analog and online ways of expressing thoughts and feelings to lost loved ones. The site offers a Private Conversations space, in which people can write to deceased loved ones in total privacy or opt to share their writing with family, friends, or therapists. The site provides a list of “conversation starters” as prompts for such writing.

3. Writing a memoir.

You may wish to share your thoughts or reflections on loss publicly, but in a more extended and polished form than a social media post would allow. This is another way to make meaning from grief and to maintain connections to deceased loved ones.

Tara DaPra has shared strategies for composing an “emotionally driven” memoir, such as one dealing with loss. Her advice is relevant for both book-length memoirs and essay- or blog-length ones (the type I’ve composed).

The first draft, DaPra suggests, may involve just getting events, emotions, and impressions down on paper without critically analyzing them, a process that can offer catharsis. Eventually, however, thoughtful reflection will be essential, she notes.

She also says, “Generating, which sometimes comes easily, other times painfully, is only the first step in the writing process. The real work is in workshop, revision, and polishing the completed work.” DaPra’s observation is a good reminder of the importance of getting feedback on any piece of writing one hopes to make public.

When it came to the loss of my parents, my most rewarding writing began as private observations and reflections that I eventually shaped into blog posts for my author website. These posts drew on memories that my parents had shared with me years before and that became part of my sense of self.

When it came to the loss of my parents, my most rewarding writing began as private observations and reflections that I eventually shaped into blog posts for my author website. These posts drew on memories that my parents had shared with me years before and that became part of my sense of self.

In my mother’s case, the memories concerned her experiences on the farm that she grew up on and that has been in our family for many years, connecting generations. In a sense, her experiences became my experiences. (Read the post about my mom here.)

In my blog about my father, I reflected on his audio recordings of his memories, which preserved both his stories and the sound of his voice. (I included clips from the recordings in the post.) Both posts honored and strengthened my bonds with my parents and helped me feel less alone with my grief. (Read the post about my father here.)

4. Addressing loss through fiction or poetry.

For me, fiction has offered a way to transcend my personal experiences with loss and, in that way, come to terms with them.

In the last year of my parents’ lives, my mother was physically disabled and suffering from worsening dementia, and my father’s increasing frailty made it harder and harder for him to care for her at the home they’d shared for many years. Hoping to address these challenges, my brothers and I got them into an assisted-living facility.

The result was a complicated brew of outcomes and emotions. My parents got exceptional care from genuinely compassionate staff. At the same time, my father grieved the loss of the independence he’d held onto for so long, and he continued to mourn the loss of my mother as he’d once known her.

As illogical as this may sound, I couldn’t fight the feeling that uprooting my parents from their old life hastened their declines: nine months after moving into the assisted-living facility, my father was gone, and four months later, my mother followed him.

After their deaths, I couldn’t get their final days and hours out of my mind, and part of all of these memories—sometimes in the shadows, other times at my parents’ bedsides—were kind and caring nurses and their assistants, in their maroon scrubs.

I found myself asking questions about these caregivers: What were they thinking about as my parents’ lives wound down? How were they able to remain so present for my folks, and for my brothers and me, during such a difficult time? In a larger sense, how did they manage to carry on with a job that required them to face, fairly regularly, the loss of people to whom they’d grown attached?

My reflections on these questions led me to write a short story told from the point of view of a nursing assistant at a facility much like the one where my parents spent their final days. The story explores how the assistant deals with the loss of a patient much like my father, and how—even while dealing with personal difficulties—she continues to show compassion for his wife and for other patients.

By assuming the nursing assistant’s point of view, I got just enough distance from my own experience to achieve a new perspective on it. I felt less alone with my grief and my sense of guilt, and I found another way to give thanks for the compassion that my parents, and my brothers and me, received at a difficult time. (The story was recently published by Smoky Blue Literary and Arts Magazine.)

Poetry can also offer a way of coming to grips with loss. My friend Beth Gylys described how composing a sonnet sequence helped her process her emotions around a death that deeply affected her and someone close to her:

“This past year, I was visiting a close friend—to celebrate the positive end of her battle with breast cancer—when her husband died of a heart attack. Though I didn’t write about it immediately (I wasn’t able to write anything for nearly a month), eventually, the poems I wrote were singularly elegiac. The poems made something…perhaps not positive, but at the least something concrete…of the profound and terrible suffering of that moment. Writing allowed me to order (at least a little bit) the chaos of that untenable time out of time when nothing made sense and when my friend’s world became consumed with unbearable pain.”

Writing About Loss Can Give You a Small Triumph Over Pain

Through writing that draws on our experiences with loss, Beth and I have been able to achieve, in DaPra’s words, “a small triumph over pain.”

In the end, this writing also freed me up to finish my novel, which was just accepted for publication, as was the story based on my parents’ final days at the assisted-living facility.

I am deeply grateful I was able to write my way through a difficult time.

* * *

Beth Castrodale’s debut novel, Marion Hatley, was a finalist for a Nilsen Prize for a First Novel from Southeast Missouri State University Press, and it was published in April by Garland Press. Her newest novel, In This Ground, was just accepted for publication by Garland Press.

Beth Castrodale’s debut novel, Marion Hatley, was a finalist for a Nilsen Prize for a First Novel from Southeast Missouri State University Press, and it was published in April by Garland Press. Her newest novel, In This Ground, was just accepted for publication by Garland Press.

Beth has published short stories in such journals as Printer’s Devil Review, Marathon Literary Review, and Mulberry Fork Review. The story referenced in “Writing Your Way Through Loss and Grief” will appear in the fall/winter issue of the Smoky Blue Literary and Arts Magazine (due out in September).

For more on Beth and her work, please see her website, or connect with her on Twitter.

Marion Hatley: To escape a big-city scandal, a Depression-era lingerie seamstress flees to the countryside, where she hopes to live and work in peace. Instead, she finds herself unraveling uncomfortable secrets about herself and those closest to her.

Marion Hatley: To escape a big-city scandal, a Depression-era lingerie seamstress flees to the countryside, where she hopes to live and work in peace. Instead, she finds herself unraveling uncomfortable secrets about herself and those closest to her.

In February of 1931, Marion Hatley steps off a train and into the small town of Cooper’s Ford, hoping she s left her big-city problems behind. She plans to trade the bustling hubbub of a Pittsburgh lingerie shop for the orderly life of a village schoolteacher. More significantly, she believes she’ll be trading her reputation-tainting affair with a married man for the dutiful quiet of tending to her sick aunt. Underpinning her hopes for Cooper s Ford is Marion’s dream of bringing the daily, private trials of all corset-wearing women especially working women to an end, and a beautiful one at that.

Instead, she confronts new challenges: a mysteriously troubled student; frustrations in attempts to create a truly comfortable corset; and, most daunting, her ailing aunt. Once a virtual stranger to Marion, her aunt holds the key to old secrets whose revelation could change the way Marion sees her family and herself.

As her problems from Pittsburgh threaten to resurface in Cooper’s Ford, Marion finds herself racing against time to learn the truth behind these secrets and to get to the bottom of her student s troubles. Meanwhile, Marion forms a bond with a local war veteran. But her past, and his, may be too much to sustain a second chance at happiness.

Available at Amazon.

Gold River: In the summer of her seventeenth year, Kit Mabek visits the site of a legendary healing river. Her mission: to find out what happened to her desperately ill mother, Ava, who vanished during Kit’s infancy. New clues suggest that Ava was drawn to the river, in search of a cure.

Gold River: In the summer of her seventeenth year, Kit Mabek visits the site of a legendary healing river. Her mission: to find out what happened to her desperately ill mother, Ava, who vanished during Kit’s infancy. New clues suggest that Ava was drawn to the river, in search of a cure.

Kit soon becomes entangled in the history of the riverside town, where she’s first seen as the ghost of Helen Wheeler, a young woman killed there years before. With the help of an old friend of Helen’s who is still haunted by her loss, Kit begins to unravel the mystery behind her mother’s disappearance. Ultimately, she discovers unsettling powers that connect her to the town’s “original water healer,” the leader of a controversial nineteenth-century commune founded at Gold River.

Get your free copy here!

References

Baikie, Karen A., and Kay Wilhelm, “Emotional and physical health benefits of expressive writing,” Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, August 2005, 11 (5) 338-346; DOI: 10.1192/apt.11.5.338.

DaPra, Tara, “Writing Memoir and Writing for Therapy: An Inquiry on the Functions of Reflection,” Creative Nonfiction, Issue 48, spring 2013, creativenonfiction.org.

Lichtenthal, Wendy G., and Robert A. Neimeyer, “Directed Journaling to Facilitate Meaning-Making.” Chapter 42 of Techniques of Grief Therapy: Creative Practices for Counseling the Bereaved, edited by Robert A. Neimeyer (Routledge, 2012).

Neimeyer, Robert A., “Correspondence with the Deceased.” Chapter 67 of Mediating and Remediating Death, edited by Dorthe Refslund Christensen and Kjetil Sandvik (Routledge, 2016).

Pennington, Natalie, “Grieving for a (Facebook) Friend: Understanding the Impact of Social Network Sites and the Remediation of the Grieving Process.” Chapter 12 of Mediating and Remediating Death, edited by Dorthe Refslund Christensen and Kjetil Sandvik (Routledge, 2016).