Hollywood isn’t known for its multi-layered box-office smashes. They don’t often make millions with metaphorical masterpieces. The general word is that Americans don’t like them. They like their stories nice and neat, simple and straightforward, properly wrapped up and sealed at the end.

Apparently, that’s why many of them scored the recent release The Grey at a B- upon leaving the theater, according to an MTV article. Too uncertain. Raised too many questions. Made them too uncomfortable.

On the contrary, I love it when a movie takes me out of my ordinary life and into something deeper, leaving me a bit shaken up. It’s at those times I feel my money was well spent. I’m left noodling over the film for hours, trying to put it together, trying to apply its message to my own life. This movie left me feeling that way. I’d have given it an A+ for that. Apparently I’m not the only one. I read critic Roger Ebert, after watching the film, was “stunned with despair.” He tried to watch another one afterwards, but had to walk out after 30 minutes. “The way I was feeling in my gut,” he writes, “it just wouldn’t have been fair to the next film.”

I walked into the restroom after the show, reliving the movie in my mind and finding again and again the deeper meanings. Another woman sat in a stall, talking on her cell phone. (Why do people think restrooms are the place to call loved ones?) The person on the other end of the line apparently asked her what she was going to see. “The Grey,” she said. “With Liam Neeson? It’s about wolves.”

I wanted to tell her. The last thing that movie was about was wolves.

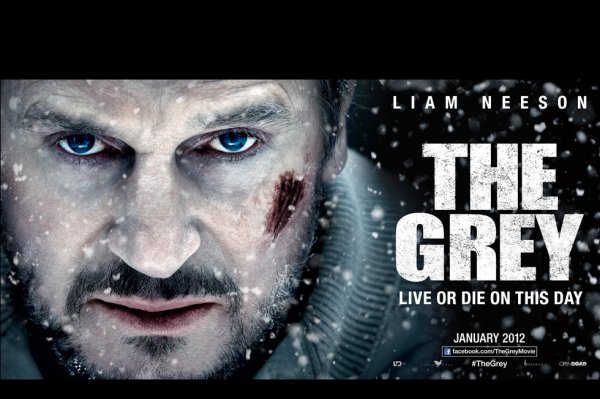

When you see the trailer, that seems to be it. Liam Neeson, in another adventure thriller, trying to survive after a plane crash in frigid northern Alaska. He and 7 other men band together to brave the elements and try to find help. The movie is filled with wolves, all kinds of them, huge, strong, snarling beasts, black, gray, and silver, praying upon the survivors, picking them off one by one as if this were Alien or Predator. But I remember thinking when I first saw the trailer: Really? Is this movie just about this guy trying to survive a series of wolf attacks?

I live in Idaho, where we’ve become really cozy with wolves again in the last decade or so, thanks to the Yellowstone transplant project. The transplant was so successful that the state experts now say we have too many of them, and they’re starting to tear down our deer and elk herds. Amid much controversy, they opened up a wolf hunt last year.

I have no romantic notions about wolves. My father, a WWII Marine and the toughest man I’ve ever known, used to speak of them with a wary respect in his eyes. I know they kill to survive, and sometimes, kill to kill. I’ve seen too many family pets, farmer’s calves and rancher’s lambs with their throats ripped out and the rest of the body left behind to think otherwise.

Whether they’d actually pursue a handful of men struggling to survive in the frigid conditions of Alaska, I don’t know. They might. I doubt they’d do so with the relentless fervor they display in The Grey. I particularly doubt that one singular alpha male would follow the main character through the mountains, across a gorge, and into a river, just to be there at the final stand. I could be wrong. Either way, it doesn’t matter, because in this movie, the wolves aren’t really wolves at all.

(Spoiler alert.)

The wolves are symbols. Stand-ins for the real main character: death.

Black and cunning, always shadowing, the wolves are always there, following the men from place to place, taking one, then another, then another. Each time a man meets a wolf, it means death has come for him. At the same time, the wolves are always there, always howling in the distance, always breaking a branch or leaving a footprint nearby. As in life, the men constantly live in the shadow of death. Thus the title—The Grey.

Each man faces death in his own way. Some are afraid, like the man suspended on the rope over the gorge. Some are oblivious, like the long-haired dude who falls behind the rest of the group. Some are weakened by disease, like the chubby man who hallucinates about his long-dead sister. Some are careless, like the man who lets his guard down to take a leak. Some just get tired and give up, content to wait for death to come.

Liam’s character, John Ottway, fights the longest and the hardest, coming back again and again to grapple with the wolves. Interesting, as at the start of the movie, he had a gun in his mouth. Distraught over having lost his wife, he’s ready to end it all, until he hears the cry of the wolf. Duty calls. It’s his job to keep the wolves away from the oil rigs. He shoots the howler, and when he comes upon it, breathing its last breaths, he remembers a poem his father wrote.

Once more into the fray

Into the last good fight I’ll ever know

Live and die on this day…

Live and die on this day…

With his hand upon the belly of the animal, he waits while the wolf dies, then affectionately scratches its head and neck, as if saying goodbye to a fellow traveler.

I wonder…does the fact that his job pulls him back from the brink of death say something about our need for purpose in life?

The poem is another place to find meaning. I was interested to discover two versions circulating about. I had remembered it as “Live and die on this day…” But I found on the movie poster on my way out, “Live or die on this day…” It was written this way on several Internet sites as well. I could swear I heard it as “and” on the movie, but I could be wrong. Now I want to see it again to find out. But with the “and,” it seems to be saying that every day, we live and we die. It’s not one or the other. We may not think about it, but each day we live our lives, we take a step closer to death.

The last scene of the movie also seems to point to this duality. Sit through the credits and you’ll see it. Man and wolf. Living and dying. Together.

Some reviewers say the movie is just a passable adventure story about men trying to survive in the Alaska wilderness. Maybe. But that’s not how it struck me. I found out later that director Joe Carnahan meant it to be something more:

“I think the movie’s about something as massive and as mysterious as life and death.”

Neeson, too, described the movie in deeper terms. He lost his own wife in 2009 to a freak skiing accident. Aside from his demonstrated skill as an actor, that could be part of why he comes across so convincing in this role.

What a pleasant and wonderful surprise. I went out to see an adventure movie. I’ve come home in a contemplative mood, having been given so much more. Strangely enough, I’m reminded of Dead Poets Society, which I just happened to catch a glimpse of on HBO last night. Coincidence?

“We’re all food for worms, boys, food for worms,” professor Keating tells his students, and then follows with this poem:

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old time is still a-flying:

And this same flower that smiles to-day

To-morrow will be dying.

~Robert Herrick

© Marcopolo | Dreamstime Stock Photos & Stock Free Images

This is a fantastic write up. Only wish I had read it BEFORE I went to see the movie. I think I would have enjoyed the movie more. Thank you.