In writing critiques, writers hear a lot about their weaknesses.

Critiques are a way of life for us. We’re always asking people what’s wrong with our work. We feel like we have to hear criticism in order to improve.

This may be true to some extent, but the longer I live the more I think that frequently seeking out “what’s wrong” can sometimes be counterproductive.

Why don’t we, for just a little bit, focus on what’s right?

Writing Critiques Often Don’t Work

Every writer has his or her strengths. We often take these for granted. Someone says, “You have great dialogue,” or “I love your descriptions,” and we tend to sort of write it off.

Great, that’s nice, but what’s wrong with the story?

Writers aren’t the only ones who do this. “[T]he sting of criticism lasts longer than the balm of praise,” say authors in the Harvard Business Review (HBR). “Multiple studies have shown that people pay keen attention to negative information.”

It’s one of the reasons why that one negative review among 10 positive ones is the one that will stick in your head and live to haunt you the next time you face the blank page.

We think all this criticism helps us write better. That may be true in some cases, but more often than not, criticism doesn’t work. Instead of helping you, all it does is discourage you.

That’s why the most accomplished writing teachers will tell you—the best way to learn is by reading. Soak in the way the masters do it. Read their work and compare it to your own.

Eventually, if you’re honest with yourself, you’ll see the difference between what you’re doing and what they do, and you’ll work to bridge the gap.

But surely having someone point out your weak plot will help motivate you to make it better?

Maybe.

Maybe not.

A Writing Critique that Includes Praise Will Do More

“It is a paradox of human psychology that while people remember criticism, they respond to praise,” write the authors in HBR. “The former makes them defensive and therefore unlikely to change, while the latter produces confidence and the desire to perform better.”

Think back to the last time you received a critique. How long did you avoid your writing? Did it take time for you to muster the courage to try again?

Now think about what happened when someone pointed out something they liked about your story. How many pages did you write that night?

“Constructive feedback, which is usually critical, rarely helps anyone,” writes executive coach and author Ray Williams in Psychology Today. He goes on to quote a number of studies showing that employee performance reviews—which are similar to writing critiques, if you think about it—do more harm than good.

“You are far better off capitalizing on what you do best, instead of trying to offset your weakness,” writes bestselling author Paul B. Brown. “Making a weakness less of a weakness is simply not as good as being the best you can possibly be at something.”

In Writing Critiques: Focus On Your Strengths

What would happen if we focused for just a bit on what we’re good at? Is it possible our writing could improve?

“Conventional wisdom says we should work on improving our weaknesses,” says business coach Gary Lockwood. “What a terrible waste of time, talent, and opportunity. Focus on your strengths.”

Still, how are we to do that when we know, instinctively, that our weaknesses are there, potentially diminishing our work?

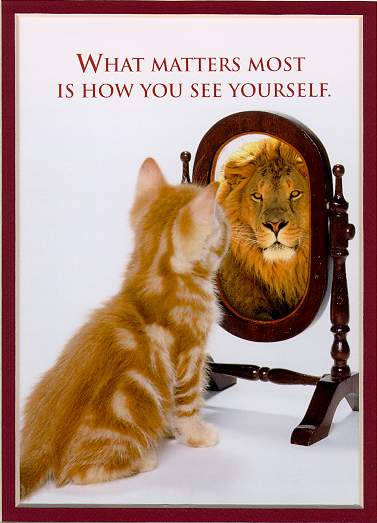

“When it comes to motivation,” writes CEO and Founder of Leadership Principles Gordon Tredgold, “this needs to be done through positive energy. We need to create a positive image and motion towards that image.”

In other words, we need to create an image of a successful writer whose work reflects our own, and then hold that image in our heads whenever we go to work.

The Image of Your Success

What does that positive image look like for you?

The easiest way to find out is to look at your writing heroes.

Find a successful author you admire—usually they will share your aptitudes, as we tend to admire people who have the same strengths as we do (even if ours aren’t as developed).

For the longest time, for example, I rejected the notion that I might be a literary writer. It couldn’t be. No way I could be writing in the same genre as my heroes. I started out with children’s stories, wrote some slice-of-life, and then moved into fantasy. But when I read that oft-repeated advice, “write what you like to read,” I’d check out my bookshelf and see them all there: the literary novels.

Yes, there were other genres. Fantasy. Thriller. Science fiction. Even some mystery. But the literary ones outnumbered the rest, and they were the ones I held closest to my heart.

As the years past and I just kept writing and writing, I wondered: Was it possible I was moving that direction?

The most recent book I sold will be marketed as literary. It’s with a literary publisher (Dzanc Books).

What sort of writing are you pulled to do? You may not feel like you’re very good at it, but if it calls you, and you admire people who write it, it’s likely your area, too.

Find your writing heroes, read everything of theirs you can get your hands on, and hold the image of their success in your mind.

7 Ways Writers Can Play to Their Strengths

In addition to finding and acting as if you are that successful writer you admire, try the following seven tips to play to your particular strengths when it comes to your work.

1. What comes easy to you?

Dialogue? Setting? Characterization? Action scenes? Romance? Think about those days when the writing just flows. What were you working on? Once you discover this, find ways to use more of it in your work.

If you love romance and you’re working on a thriller, maybe you need to reconsider your genre—or maybe you need to up the romance factor in your current work…a lot.

2. What do others like about your writing?

Go back to your writing critiques and find those things people praised you for. (Likely you’ve forgotten all about them.) Ask your first readers. Look at the comments people have made about your published works. What’s working for you? Make note of those things so you can do them more often.

3. What do you hate to write?

You probably know this one easily. This is the one that frustrates you to no end and leaves you writing maybe one word every fifteen minutes. If you type furiously when the hero is fighting the dragon, but find you just can’t get the words out when the hero is fighting with his father, your story may need to focus more on the dragon scenes.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t write what’s hard to write. I’ve often found some of my best writing occurred on those pages I bled through. But I’ve also tried writing something like a memoir, and though my first readers loved it, I hated it. I didn’t like writing about something that had already happened. I love the discovery of writing, so I’ve focused on purely fiction instead.

You know what may be just “difficult” to write, and what you “hate” to write and could never finish even if you had a gun to your head. By all means, avoid that type of writing and go with what works for you.

4. Which of your own scenes move you?

When you re-read your work, what moves you? Forget about what you think sounds good or may impress an editor. What moves you, personally?

Is it a scene that involves loss? Does it have to do with family life, injustice, or the pains of growing up? Do you write best about relationships, or are you at your forte when weaving a puzzle for the reader to solve?

Some of my favorite writers explore the same themes over and over again. It doesn’t mean they’re formulaic—they just know what works for them.

I’ve heard it said that as writers we don’t really have a choice in the themes that we explore. They come out unconsciously whether we like it or not. I think this happens only as we find and trust our own voices.

To do that, we have to play to our strengths—write what we’re pulled to write, not what we think we should write or what someone else advises us to write.

5. Work around your weaknesses.

We can all get a little better at those things we have trouble with, but the truth of the matter is that we’ll probably never get great at them. That means we may want to find ways to get around them.

A manager who hates dealing with numbers, for example, is probably better off dealing with them as little as possible. In addition to hiring an able accountant, he may decide to look at facts and figures only in the morning, when he’s fresh.

If you’ve got a scene coming up that you know is hitting a weak spot, find a way to help yourself. Tackle it when you’re feeling especially creative, maybe. Let’s say it’s a murder scene and it makes you horribly uncomfortable. Find some articles and books about writing a kill scene and study before you write. Try to get yourself “in the mood” in another way—write in a dark room, with only a candle. Put on some eerie music. Put the weapon in your hand and imagine the scene.

Ask a writing buddy to get together with you to talk out the scene. Read other murder scenes and take notes on how they do it.

Do anything you can to get yourself through—and then remember that murder is not your forte, and try to avoid it in the future.

6. Get help.

Successful people of every type get help along the way. We all have weaknesses. If you know yours is dialogue, why not swap first reads with a writer pal who has great dialogue skills? Or hire an editor who excels at dialogue?

Most likely, you know well where your weaknesses are. Rather than beat yourself over the head, draft those sections as best you can, and then consider getting some help to polish them up before you submit.

7. Try a tool.

Writers of today have a lot of tools at their disposal—including software that can help you craft a story. Terrible at coming up with names? There’s an app for that, and just about everything else.

Do you talk out your stories better than you type them? Try some voice recognition software. Have trouble plotting? Try Scrivener or StoryBlue.

To help you get started finding software that works for your writing style, check out graduate student Kelly Hanson’s article on “Adapting Your Writing Software to Your Writing Style,” and then be sure to do your research. Here’s a handy Creative Writing Software Review.

In the end, critiques have their place, but if you find yourself getting mired down by all your “weaknesses,” take some time to really focus on your strengths, and let them guide you where your writing needs to go.

Note: For help in using your strengths to build your author platform, see Writer Get Noticed!