According to PBS, Herman Melville first thought of the idea for what would become Moby Dick after reading a 1839 article by Jeremiah N. Renolds entitled “Mocha Dick: Or, the White Whale of the Pacific.”

For years he researched and thought about the story. It wasn’t completed and published until twelve years later, in 1951.

J. R. R. Tolkien took 12 years to finish Lord of the Rings; Margaret Mitchell 10 to write Gone with the Wind; Michael Crighton eight to finish Jurassic Park.

Not all of that time was spent at the notebook or typewriter. Much of it was spent researching, thinking, incubating.

In today’s world of print-on-demand publishing and instant access to ebooks, many authors are being encouraged to hurry hurry hurry, get the next book out to keep their names in readers’ heads. It can be hard to imagine spending over a decade on one book. Professional suicide, right?

But for some of us, speed just isn’t something we can manage well—not and still be happy with our work. Should we feel badly if we take a little longer than might be advisable in today’s world?

I wondered about that, so I went researching. Turns out that the so-called “incubation period” is key to creativity, and exactly how long that period ends up being can vary from person to person and even from work to work.

Here’s more on this important part of the creative process, and why each writer needs to find peace with his or her own quirky way of incubating.

When that “Aha” Moment Takes Longer to Appear Than We’d Like

Author Susanna Daniel called it “The quiet hell of 10 years of novel writing.” She started her first novel, Stiltsville, in 2000, and spent the next decade in what she also calls a state of “active non-accomplishment.” The book was published in 2010.

During those years she wasn’t always writing, but she was thinking about the novel. Most likely, she was in the period psychologists call incubation.

During those years she wasn’t always writing, but she was thinking about the novel. Most likely, she was in the period psychologists call incubation.

Look up the word “incubate” and you find something about sitting on eggs until they hatch. Second definition: to be infected with a pathogen before showing signs and symptoms of disease.

Hmm. We could draw some interesting parallels between these two definitions and what it is to write a book. But let’s move on down to the third definition, where we come a little more clearly to what we’re talking about:

to form or consider slowly or protectively (emphasis mine).

Social psychologist Graham Wallas described it back in the 1920s as the second stage of creativity (after preparation and before illumination and verification), when we actually let go of the work or the idea for it and stop consciously thinking about it. Doing so allows the brain to summon the sub-conscious mind to do its magic.

This is that period where you go for a walk, take a hot bath or shower, or simply take the weekend off from your project to do something fun. How often during these periods have you experienced that “aha” moment when something you’d been struggling with suddenly became clear?

“This is a fascinating capability of the mind,” writes psychologist Dr. Jeremy Dean. “It’s wonderful that it can solve problems unconsciously while we’re getting on with day-to-day life.”

What if that moment doesn’t come as quickly as you’d like?

Well, there’s no guarantee that you’ll experience that breakthrough moment (or “illumination” as psychologists call it) anytime soon after preparation. In fact, Wallis himself said the incubation process could last for years.

In a 2014 study review, researchers noted that in scientific study of creativity, incubation periods varied from a few moments to overnight to several weeks before a problem was solved. Short periods of incubation are linked with “mind wandering,” those times when writers and other creatives find themselves staring out the window. (Yes, we are working when that happens.)

Sleep correlates with a longer period of incubation, and has shown in several studies to enhance creativity and lead to “spontaneous” problem-solving.

Yet it’s true that the incubation period can last much longer than overnight or even a few weeks, particularly if we’re wrestling with a big problem that may be composed of many smaller ones (as often happens in a novel, for instance, or musical work), or if life happens to interfere with our ability to keep the problem in our heads.

Turns out that longer incubation periods are totally normal.

Difficult Projects Make Us Better Writers

In a 2009 study on incubation and problem-solving (and what are we doing as writers if not solving problems in our stories?), researchers noted that sometimes long incubation periods were more effective than shorter ones:

“Longer incubation periods may allow additional problem-solving activity or a greater degree of forgetting of misleading items or spreading of activation memory. Thus, problem solvers may show a larger performance improvement when they return to the problem after a long incubation period than after a short one.”

They go on to quote some studies supporting this view, but then admit that currently, there are no standards to define “long” or “short” incubation periods—and that the nature of the problem and the length of the preparation period should be taken into account when determining the length of the incubation period.

In other words, if you’re working on a project that required a year of preparation, in terms of research, for example, you may expect that your incubation period on the project—that time in which your unconscious mind goes to work putting it all together and coming out with something that will work as a story–might be longer, too.

How often you fail at the creative process must also be taken into account. My current work in progress has kicked my butt a number of times, as potential plots were devised and discarded. It can be tempting to think of all these trials as the path to overall failure, but on the contrary, researchers say that they’re important to the process as a whole.

Failing to solve the problem we’re presented with helps us learn. In fact, when we get “stuck” on something and eventually find our way out—however long that takes—we cement what we’ve learned a lot more firmly than when we breeze through. That story that takes you forever to figure out, for example, could be the one that teaches you the most about writing in general.

When we get “stuck” on something and eventually find our way out—however long that takes—we cement what we’ve learned.

Some studies have even suggested that we perform better with longer preparation periods and longer incubation periods—particularly if we’re dealing with creative rather than linguistic or visual problems. In fact, going back and forth between preparation (research) and incubation (walking away from the problem) are proven ways to get to a creative solution:

“When solving a creative problem,” wrote the researchers in that 2009 study, “individuals benefit from performing a wide search of their knowledge to identify as many relevant connections as possible with a presented stimuli. Each time individuals reapproach the problem, they improve their performance by extending the search to previously unexplored areas of their knowledge network. Incubation appears to facilitate the widening of search of a knowledge network in this fashion.”

In other words, your best story may just require more time.

The Incubation Period in the Writer’s Career

This whole process applies not only to each work we attempt, but to our writing career as a whole.

Award-winning business coach Carolyn Ellis defines incubation as that period of time when we maintain “optimal environmental conditions for growth and development.” Much like a caterpillar in a cocoon, the incubation period can go on and on with no indication of an end.

“Stillness. No action. No discernable progress. Dissolving. We can’t see what’s happening, but from deep within some massive shifts are actually happening and all the caterpillar can do is just hang in there (literally!).”

This period of “no discernable progress” can occur while we’re working on something, but I also believe it occurs at various periods in our lives, when we’re moving toward something but we can’t tell if we’re really getting anywhere or not. For many of us, that can lead to discouragement, particularly if we’re goal oriented, driven people.

Never doubt that there is value in that swamp filled with the weeds of thinking and reflecting and problem solving and failing and trying again. It may all seem to take longer than you think it should, but most likely you are learning during the process, even if you may not realize it. The truth is that this idea of having to create something on a clock—or even “become” something in a certain time period (like a bestselling author)—is a fairly new “requirement” in our current culture.

“Incubation takes the time it takes,” writes Ellis. “I’m sure that when Michelangelo carved his famous David statue he never looked at his watch, tapped it and said, ‘Dang, I’m behind schedule! Creating this master work of art is taking too long!’”

Yet we often feel just that, don’t we? We’re supposed to produce a book a year, or two books a year, or whatever arbitrary productivity measurement has been placed in our heads. We’re supposed to sign a publishing contract within five years of trying this writing thing. We’re supposed to sell thousands of copies by our third book. Whatever it is, realize that these are all made up standards that we can choose not to pay attention to.

Granted, many authors feel pressed to produce to get money into the checking account. Money is a whole other beast that I won’t go into on this post, but suffice to say I understand this motivation, but that it may interfere with your creative goals.

It can also leave you feeling like a failure when in fact you may be getting better every day.

Consider the budding young artist who dreams of the New York Times bestseller’s list, but ten, fifteen, or twenty years later, has yet to land a publishing contract. Then, one day, it happens, and as he prepares for the release of that first novel, he looks back on that long period—during which he most likely thought about quitting several times, or at least wondered if he would ever reach his goal—with new eyes. Suddenly, he realizes he needed all that time to become the writer that he is now, to develop his talent and his vision to the point of landing that contract he’s long sought out.

Time. It’s one thing most of us feel we don’t have these days, but it’s also the one thing that can take us where we want to go, if we can be patient. In the Harvard Business Review, professor and author Terese Amabile writes that any professional will be more likely to experience creative success “if she perseveres through a difficult problem,” and that indeed, “plodding through long dry spells of tedious experimentation increases the probability of truly creative breakthroughs.”

Experimentation. Research. Incubation. Trying again. All this takes considerable time to complete. Time for each project, and time to build project upon project for a successful creative career.

“This business absolutely does not happen overnight,” writes author and screenwriter Michele Wallerstein. “Becoming a professional writer takes a very long time. It takes the tenacity to write script after script after script to become a decent writer. It takes dozens of meetings to sell an idea….Following your dream is a wonderful thing, but you need to have a great deal of determination to see you through the lean years.”

But we’re impatient, aren’t we? We want that success now. And many of us are being told that it awaits us, if only we’ll hurry along toward it.

The Danger of Writing Faster

Write faster, they say.

Google those two words and you’ll find article after article telling you how to churn out the words in less time. For some people, it totally works. I know some professional writers who can produce stories at amazing rates. I know others who thought they were slow writers, but when pushed by deadlines, responded with completed projects faster than they ever thought possible.

There’s something to be said about fast writing. Sometimes it allows us to push past the inner editor and get to the good stuff in a less inhibited way. We may produce some really creative stories just burning through the pages for an hour or so. Some authors can do that and then sell the results and move on happily through their careers.

“The argument for writing books faster,” says author Holly Robinson, “is that your readership grows exponentially with each book. Fans of your first book will be more likely to read your second one, and readers who discovered you with your third book will, if they liked that novel, go back and read your other two. If you take too long to publish your next book, there’s some chance your readers will forget all about you—or so goes the thinking among those marketing books these days.”

You may find value in trying to be a faster writer for a short time—you may even discover something new about yourself in the process. But if you come up against a wall of frustration that only ends up discouraging you, or if you find that your projects just aren’t what you’d like them to be, or you’re not experiencing the success you thought you would, it may be time to re-evaluate this whole “faster” idea.

“On the other hand,” says Robinson, “those who write their novels too fast, without the necessary revision and editing steps, are in danger not only of alienating readers who are disappointed in the end product, but also at risk of losing themselves as authors and artists.”

That’s where the real danger lies, I think—in what happens to us as artists. Fast writing works well for some, but if you’re experiencing negative symptoms, such as fatigue, writer’s block, discouragement, or even apathy, it could be one of the worst things you ever tried.

I know that for me, personally, my process requires a longer incubation time. I have to stir the story over in my mind, experiment with this or that approach, write a bunch, and then stir some more, before I land on something I’m (mostly) satisfied with.

Maybe one day that will change. But in the meantime, I think it’s good to know that for larger projects, at least, extended periods of preparation, incubation, and illumination are completely normal parts of the process—and may be required parts of the process for you and your creative career.

If so, you can count yourself in good company.

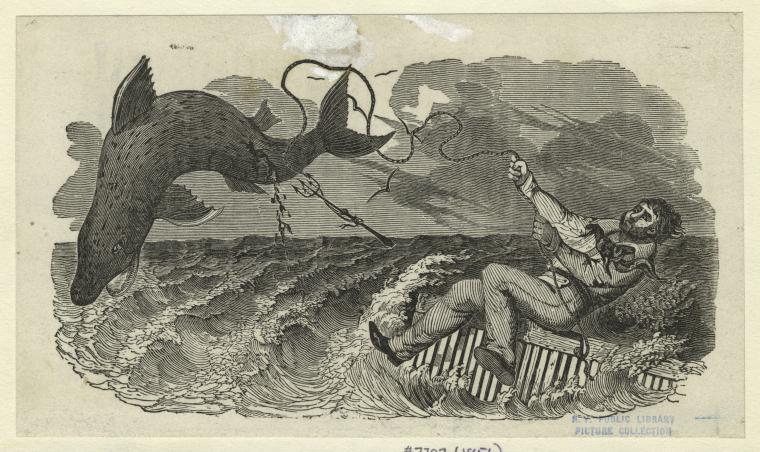

To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be that have tried it.

~Herman Melville

Have you felt pressured to hurry along your writing/creative projects? Please share your thoughts.

Last photo: Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1856). Tales of the ocean. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-0d73-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Sources

“Biography: Herman Melville,” PBS, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/whaling-melville/.

Susanna Daniel, “What Took You So Long?” Slate, July 16, 2010, http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2010/07/what_took_you_so_long.html.

Jessica Stillman, “The 4 Stages of Creativity,” Inc, October 1, 2014, http://www.inc.com/jessica-stillman/the-4-stages-of-creativity.html.

Maria Popova, “The Art of Thought: Graham Wallas on the Four Stages of Creativity, 1926,” Brain Pickings, https://www.brainpickings.org/2013/08/28/the-art-of-thought-graham-wallas-stages/.

Dr. Jeremy Dean, “The Incubation Effect: How to Break Through a Mental Block,” PsyBlog, July 25, 2012, http://www.spring.org.uk/2012/07/the-incubation-effect-how-to-break-through-a-mental-block.php.

Simone M. Ritter and Ap Dijksterhuis, “Creativity—the unconscious foundations of the incubation period,” Front Hum Neurosci. 2014; 8:215, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3990058/.

Carolyn Ellis, “The Magic of Incubation: 3 Steps to Staying Sane When Your World Seems Upside Down,” Brilliance Mastery, April 2015, http://www.brilliancemastery.com/blog/the-magic-of-incubation-3-tips-to-staying-sane-when-your-world-seems-upside-down/.

Terese Amabile, “How to Kill Creativity,” Harvard Business Review, September-October 1998, https://hbr.org/1998/09/how-to-kill-creativity/ar/1.

Michele Wallerstein, “The Business of Your Writing Career: 10 Things You Need to Succeed as a Writer,” ScriptMag, January 20, 2013, http://www.scriptmag.com/features/10-things-you-need-to-succeed-as-a-writer.

Ut Na Sio and Thomas C. Ormerod, “Does Incubation Enhance Problem-Solving? A Meta-Analytic Review,” Psychological Bulletin, 2009; 135(1):94-120, http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~unsio/Sio_Ormerod_meta_analysis_incubation_PB.pdf.

Holly Robinson, “How Long Does a Novel Take to Write?” Huffington Post, May 20, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/holly-robinson/how-long-does-a-novel-tak_b_5359814.html.

Great point! I know authors can feel rushed to push out sequel after sequel, and even when they do it well, it can take the joy out of writing for them. I would much rather take my time and write a book that is all it can be.

I just love this, Colleen! What I know for true is that any creative work, when hurried, loses so much more than is gained. And we know through so many studies that creativity is fostered in the “slow” times.

I simply love, “Never doubt that there is value in that swamp filled with the weeds of thinking and reflecting and problem solving and failing and trying again.” So very true.

My current novel has been in the works for 7 years 🙂

Thanks, Susan! So many of us in the swamp, eh? :O)

I could not love this article any more! I am going to bookmark it, and every time I beat myself up for not being a fast writer, every time that “ah-ha!” moment takes days or weeks instead of minutes, every time someone asks me why my novel isn’t finished yet, I’ll read this to remind me that creativity needs incubation time and that’s what’s happening. Thanks so much!

So glad, Heather! Ha ha. My “ah-has” have been taking months lately! :O)

I am glad to hear about the incubation period in a writer’s life. I have been writing (and rewriting) my book for over five years. It is now over 400 pages and I want to reach the conclusion soon. I see the danger of writing too fast and not letting myself make the ending without going through the process of illumination to make my book worthwhile to readers. Thanks for the encouragement to let my creative juices mull over each scene and make my work the best that I can write.

So glad if it was helpful, Kathy. Best of luck to you on your project! Time spent so carefully crafting is never wasted.