I was a player of an MMORPG [massively multi-player online role-playing game] called “City of Heroes.”

This was a game where you would create a character by putting together how they looked from a collection of parts, decide what kind of superpowers they had, write out their biography in a little box specifically provided for that purpose, and then go run/jump/fly around in a game world and punch bad guys with friends.

The thing about this game in particular was that it encouraged a lot of creativity. People would hold costume contests, you might receive compliments on a particularly well-written biography, and there was a large role-playing community—of which I was a part.

When A Game Shuts Down, What Happens to the Characters?

This was improvised acting: you created a character and a role, communicating through a combination of text, emotes, judicious use of powers, and basic motion, and you would work together with other players to craft collaborative stories. You could even build customized bases and missions to help fill out the events you wanted to portray.

Some people would make pretty amazing stuff, epics that took months or years to play out fully. That community was the primary reason I played the game. They were awesome.

The game shut down in 2012. It happened suddenly—almost overnight—and with little explanation.

I wasn’t as devastated as some who had character histories stretching back ten years, but it was still difficult. I’d met friends through that game—heck, there are people who met their spouses through that game—and there were a lot of interesting characters who seemed like they would just vanish into the ether.

That didn’t seem fair.

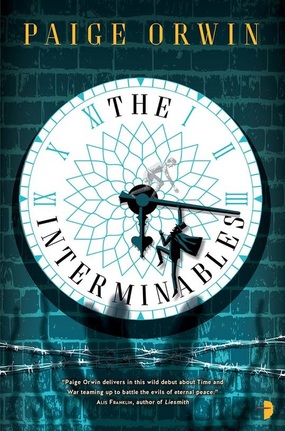

So… I decided to build a new home for some of them. That was the genesis of The Interminables. It’s changed since then, of course, but in essence the book began as a lifeboat for fictional characters.

How Do You Accurately Portray a Character You Learned to Hate?

The biggest trouble I had was with a particular character. There is a…. well, it isn’t a love triangle, exactly, but a similarly complicated situation in the book that’s based on the original character dynamic that played out in City of Heroes. Basically, one character is in love with another character who is in love with someone else, and the last character hates the first character.

Now, the thing about online role-playing is that you can only play one person at a time. You can have more than one, but short of buying two accounts and having two computers, you could only be one character. Everyone else was controlled by other people.

In this specific instance, I was playing the character that was hated. This meant that I only ever saw the side of the “hater” character that disliked my own, and relatively little of her positive qualities. Later, when writing the book (after getting permission to base the book character on the game character), I had extreme trouble portraying her in any kind of positive light—even when writing from the POV of the character that loved her!

It took a long time to figure her out. Months, at least. I had to hunt down testimony by other folks that had interacted with her in other situations (you could keep a “log” of in-game conversations, which helped), and think long and hard about her motivations and core qualities.

Where was she coming from? What did she believe? Why did she act like that, and what did she think of her own actions?

Over time, I grew to understand and even like her…. but for a long, long time, she was the worst.

Why Wouldn’t I Write What I Wanted to Write?

After over a year of work, I ended up rewriting the entire plot, dropping half of the characters, and alienating friends who had hoped to see their characters and ideas in the book.

This was hard. I had worked with these people for a long time, and they weren’t bad ideas or bad characters…but as the manuscript grew more and more sprawling, and started losing its focus, and as I got frustrated with the spotlight wavering between so many places, I had to face the notion that this was my work.

I was the one writing it.

I was the one who had to do all of the actual labor. Why shouldn’t I be writing what I wanted to write?

I wrote out an entirely new outline, cutting out everything that I was having trouble with, and worked up the courage to say that I was changing things. My friends were shocked, and hurt. They felt betrayed. They tried to tell me that I could make it work, if I would only….

I didn’t.

Things have never been quite the same between me and the affected parties—we’re more distant now, with no collaboration on what finds the final pages—but we have made up, and I’m glad for that.

If I’m Going to Write Dark, It’s Nice to Know I’m Good At It

I’ve been told that I do an excellent job portraying depression. That the book holds a “knowledge of suffering,” capturing longing without being melodramatic, that there’s a “PTSD fugue” strain in the writing that underpins everything. There are reviews that say that the book is unexpectedly dark, despite its superheroic origins and zany monsters.

On one hand, it’s hard to imagine how it could be anything else: one of the main characters, after all, is a hundred-year-old wizard who has seen some sanity-breaking crap and actually does suffer PTSD, and the other is a ghost who, in addition to being dead, is a personification of World War One (and we all know how delightful that was).

On the other hand, when I started writing it, I myself was dealing with depression. I’d just dropped out of college after returning from a year abroad where I’d lived through an earthquake and the (unrelated) deaths of people in both of my host families. My own family had recently disintegrated after a divorce and I was bouncing between two households.

I was on medication. I was unemployed, and then employed in retail, and then unemployed again. I went through a brief and intensely stressful failed relationship. Things only started looking up again when I finally returned to school, confessed to my current (and awesome) partner-in-crime, and managed to snag my splendid agent Sara Megibow.

It was tough, is what I’m saying. Sometimes it’s still tough.

But, when I tap into that personal experience, I do my best work. There are passages in The Interminables that I cried while writing. Those are the sections that required the least revision. The book became a story about perseverance, about taking solace in the small things, about doing the best you can even when everything—even your own mind—seems out to crush you.

Not that it’s all gloom, but it’s nice to know that if I’m going to write “dark,” at least I’m good at it

Writing the Novel Helped Me Learn How Emotions Work

[Through writing the book,] I learned how emotions work.

I have always been terrible at determining my own feelings. It’s very hard for me to tell people “ah, yes, I’m sad,” because whatever internal sensors I have just register a confused muddle. I often wished I could just shut emotions off, because they weren’t helpful, anyway, and I couldn’t control any of them. It still isn’t uncommon for me to do things like forget to eat.

Also, believe it or not, I had no idea how to portray romantic love when I started. I had no idea what that felt like. I’d seen it in movies and everywhere else, but actually writing about it was confusing and intimidating and I was terrified that I would get it wrong.

I hated writing physical descriptions of characters. I worried that any attempt at noting attraction was too obvious, or too crass. In the original City of Heroes format, none of my characters had ever pursued any kind of romance. It freaked me out. Thus, I bulled through the not-a-love-triangle in Interminables with the use of copious research.

I looked at the psychology of it. I asked friends what it felt like. I tried to understand what made people attractive, and how that was expressed.

The book has been called “disjointed,” and I think part of that might be because it’s written from a very, very close angle: close enough to see how emotion distorts perception, to note the sudden changes in thought when circumstances interfere, to deliberately miss things that otherwise should be obvious.

I couldn’t make sense out of how characters should act otherwise. I needed the emotion to be visible, to have its own logic, and ultimately to drive what they did in a manner that met all the checkboxes for “realistic.”

I’ve been told since that I’m much better at “getting” people. It’s apparently just a matter of taking all of these various drives into account rather than accepting what people do or say at face value. Who knew?

When I Find Excuses to Avoid Writing, I Feel Guilty

I… don’t know [if writing is a spiritual practice for me].

I know that when I don’t do it, I’m unhappy. When I find excuses to avoid it, I feel guilty.

When I do write, and I get in the zone, and I get a lot done, it lets me stave off that guilt for a little while, and not feel like a waste of carbon and other common elements. It feels like what I should be doing, even if it isn’t what I want to be doing right at that moment (though I should feel like I want to do it, given that it provides a sense of assurance that I’m good at something, and a hope for a future that isn’t office work).

It doesn’t feel like transcendence, perhaps because it would feel pretentious and unworthy of me to claim that I’m some sort of channel for a divine power. It doesn’t feel like grace, because I’m not thankful enough for it, and also because it’s very hard not to seek outside validation.

It’s what it is. I’m a lapsed Catholic; maybe that’s why so much of it revolves around guilt.

The Sequel Has to be Done When?

I have a sequel in the works that needs to be finished by a certain deadline. This terrifies me.

The notion of putting out a bad sequel, and letting people down, terrifies me.

The idea that this is what it’s like to be a published author—on deadline, always worried about quality, never feeling good enough—it’s what it’s like, always, for everyone in the industry, terrifies me.

I still want to do it.

* * *

Paige Orwin was born in Utah, to her great surprise. At the age of nine she arranged to rectify the situation. She now lives in Washington state, next to a public ferry terminal and a great deal of road construction, and has never regretted the decision.

Paige Orwin was born in Utah, to her great surprise. At the age of nine she arranged to rectify the situation. She now lives in Washington state, next to a public ferry terminal and a great deal of road construction, and has never regretted the decision.

She is the proud owner of a BA in English and Spanish from the University of Idaho and happens to have successfully survived the 8.8 Chilean earthquake in 2010, which occurred two days after her arrival in the country (being stubborn, she stayed an entire year anyway).

She began writing The Interminables when her favorite video game, City of Heroes, was shut down in late 2012.

Her partner in crime wants a cat. This, thus far, has not happened.

Read more about Paige on her website, or connect with her on Twitter.

The Interminables: It’s 2020, and a magical cataclysm has shattered reality as we know it. Now a wizard’s cabal is running the East Coast of the US, keeping a semblance of peace.

The Interminables: It’s 2020, and a magical cataclysm has shattered reality as we know it. Now a wizard’s cabal is running the East Coast of the US, keeping a semblance of peace.

Their most powerful agents, Edmund and Istvan — the former a nearly immortal 1940s-era mystery man, the latter, well, a ghost — have been assigned to hunt down an arms smuggling ring that could blow up Massachusetts.

Turns out the mission’s more complicated than it seemed. They discover a shadow war that’s been waged since the world ended, and, even worse, they find out that their own friendship has always been more complicated than they thought. To get out of this alive, they’ll need to get over their feelings, their memories, and the threat of a monstrous foe who’s getting ready to commit mass murder…

Available at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and wherever books are sold.