We all know that negative self-talk can be destructive.

Most of us are much meaner to ourselves than we ever would be to a friend. When a story is rejected we privately bash our own writing ability. When we fail to stick with our writing commitments, we bemoan our own lack of discipline.

“You’re so lazy. Will you get with it?”

No doubt you’re familiar with these concepts, but you’re probably still allowing some of these negative statements to live inside your thoughts. To help you make real, practical changes, I’m going to give you some straight-up examples of things most writers usually say to themselves, and what they should say instead to boost motivation, creativity, and productivity.

But first, a bit more about this language thing, and why it’s so critical that we improve it if we’re interested in reaching our full potential as writers.

Self-Talk: The Words We Use Affect How We Think

Self-Talk: The Words We Use Affect How We Think

The language we use affects how we think.

You may already know this on an intellectual level, but it can be tough to internalize it.

Our natural instinct is to believe that we think, and then we talk out those beliefss. But studies have shown that in many cases, we actually think in terms of the language we normally use, so that our words lead the way.

The idea that language leads thought has been around for decades. Most believe it began with linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf in the 1940s, who theorized that language had a certain power over the mind, and that if one didn’t have a word for a concept, one couldn’t successfully think about that concept.

His theory was later abandoned based on lack of actual studies to support it, and because we know we can think about things even if we don’t have words for them. But now more recent research has revived the general idea that language can shape our thought processes and our experiences to some extent.

Different Cultures Have Different Languages—and Different Ways of Thinking

Professor Lera Boroditsky, in her studies of the Kuuk Thaayorre people who live in northern Australia, found that they have a more defined language when it comes to spatial concepts than English-speakers do.

Instead of using right, left, forward, and back to define where something is in relation to the speaker, the Kuuk Thaayorre use north, south, east, and west.

Instead of saying, “move the cup to your right,” they would say, “move the cup northwest a little.”

How does this affect their thinking? For one, these people can orient themselves in terms of direction no matter where they are—even if they’re inside a building.

For another, they order events in terms of direction. If given four pictures of a man aging, an English speaker would arrange them from left to right—baby to boy to man to old man. Hebrew speakers will arrange them from right to left. The Kuuk Thaayorre arranged them from east to west, no matter in which direction they were facing.

Says Boroditsky, “That is, when they were seated facing south, the cards went left to right. When they faced north, the cards went from right to left. When they faced east, the cards came toward the body and so on. This was true even though we never told any of our subjects which direction they faced.”

Self-Talk: How Are Your Words Affecting Your Thoughts?

It’s interesting, because in a way, English speakers orient themselves based on ego—something is to the left or the right of where I am standing. The Kuuk Thaayorre don’t bring ego or self into it—they orient themselves based on the space around them.

You can see how this would reveal different patterns of thinking.

Another example: English speakers talk about time with spatial metaphors: “The worst is behind us.” Mandarin speakers talk about time with vertical terms: “Last month was a down month.”

English speakers talk about duration of time in terms of length: “That was a short movie.” whereas German speakers talk about duration in terms of amount: “That was a big movie.”

Even just trying on these alternate statements for size can slightly alter how you think about the event.

Self-Talk: Changing Your Words Can Change Your Outlook

Self-Talk: Changing Your Words Can Change Your Outlook

If you didn’t speak English, but were taught English words to describe certain objects, would your native language preferences still shine through in your thinking? Boroditsky found that the answer was “yes.”

Unlike in English, many foreign languages assign a gender to the words for inanimate objects. Boroditsky and colleagues taught German and Spanish speakers some English words, then asked them to describe objects in English that would typically have a gender assignment in their native languages.

When describing a “key,” for example, which is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish, participants used English words that matched the gender assignment from their native language. Germans used “hard,” “heavy,” “jagged,” and “metal” and Spaniards used “golden,” “intricate,” “little,” and “lovely.”

Studies of art have also shown this gender assignment to come through on the canvas. When looking at whether “death” was portrayed as a man or a woman, researchers found that in 85 percent of the cases, the answer was predicted by the gender of the word in the artist’s native language.

Most German painters made death a man, while most Russian painters made it a woman.

How We Describe Things Affects How We Think About Them

These differences in language and in how we describe things can significantly affect how we think about them. Imagine how your thoughts and feelings would change toward the idea of death if you were thinking of it as male, rather than as a female?

Other studies have shown that our language can require us to pay more attention to some things, and less to others. In languages that require gender assignment, for example, you’d have to reveal that you spent time with your female friend, whereas in English, you could simply say you spent time with your friend and it’s nobody’s business what the friend’s gender was.

You would, however, have to reveal the basic timing of the event in English. “I saw my cousin (past tense).” In Chinese, however, you can use the same verb for past, present, or future, keeping the time of the meeting to yourself.

(Is it any wonder then we English speakers are so obsessed with time?)

Self-Talk: How to Rephrase Statements You Make About Writing

Self-Talk: How to Rephrase Statements You Make About Writing

Let’s apply this idea to the language we use as writers, and see if we can change the way we think about things, and thus improve our ability to deal with all the different facets of the writer’s journey.

“Rejection,” for example, is a big word in the writer’s language. We’ve all received rejections of our work, and we’ve all felt badly because of them.

“Rejection” brings up all sorts of negative thoughts and feelings. A writer may feel unwanted, like she doesn’t belong, that she’s not good enough, or that her work isn’t worth anything.

What if we rephrased rejection? What if, when receiving that dreaded rejection letter or email, we described it as a “redirect” letter or email instead?

“I just got a redirect letter. Time to submit my work to that other publication.”

“My redirect email let me know that I’d submitted to the wrong place.”

This is a small change, but notice how it can alter your thinking. This letter is no longer about the quality of your writing or whether you have writing talent—it’s all about where you submitted the piece. Further, it directs you to submit somewhere else.

This sort of language makes it clear that you simply need to submit the piece to a publication that is more likely to accept it. No need for emotional angst, depression, despair, or any of the other icky feelings that usually accompany this sort of letter.

Changing the Way You Phrase Things

Here’s another example: Instead of calling a one-star review a “negative review,” how about we call it a “not-for-me” review?

A negative review again puts all the emotion on the work. You feel like a pincushion where every unflattering word is a personal stab with a small sharp object. You suffer pain and remorse and may question your writing ability and talent. The experience may be so difficult that it slows your progress on your next work.

A not-for-me review, on the other hand, puts the review back in the reader’s court. The book simply was not for him (or her). Instead of sounding like something is wrong with your book, it simply sounds like book and reader didn’t match up.

This is a much better way to put it, as a) it’s probably true—the book just wasn’t one the reader liked, for whatever reason, and b) it takes the personal sting out of it. It’s not about you at all. It’s about what the reader likes.

See how this works? Can you feel the relief that the improved phrases offer you? Can you imagine how you could recover more quickly from what are typically considered difficult experiences in the writer’s life if you simply used different words to talk about them?

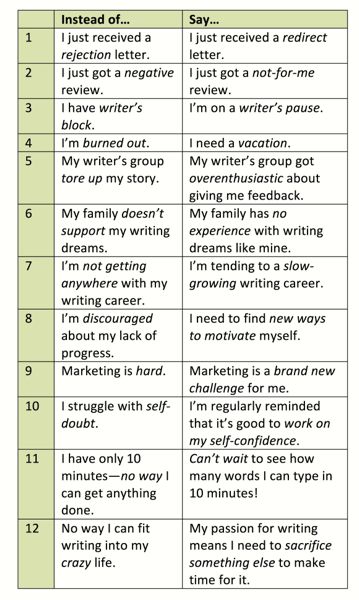

Self-Talk: 12 Ways to Rephrase Common Writer Statements

I’m going to take this a bit further and offer you some other wording alternatives. If you think of more, please add them in the comments below.

Do you have other ways to rephrase things you regularly tell yourself about writing?

Sources

Joshua Hartshorne, “Does Language Shape What We Think?” Scientific American, August 18, 2009, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/does-language-shape-what/.

Betty Birner, “Does the Language I Speak Influence the Way I Think?” Linguistic Society of America, https://www.linguisticsociety.org/content/does-language-i-speak-influence-way-i-think.

Guy Deutscher, “Does Your Language Shape How You Think?” New York Times, August 26, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/29/magazine/29language-t.html.

Lera Boroditsky, “How Does Our Language Shape the Way We Think,” Edge, June 11, 2009, https://www.edge.org/conversation/lera_boroditsky-how-does-our-language-shape-the-way-we-think.

Yet another fantastic article, Colleen. In addition to the really wonderful practical advice, your introduction about the nuances of different languages and how that affects the perspective of the speakers was fascinating. And eye-opening.

I’ve been taking a much-needed vacation and working on strengthening my emotional resiliency to the rigors of professional writing, so this is well-timed. I’ve also taken a cue from HM Ward, who’s gone from working 120 hours a week to 20 hours a week, while still getting almost as much done as before. My research into the principles that made that possible for her has been encouraging.

Thanks for another great read!

Thanks, Donna! I like the way you put it: “strengthening my emotional resiliency.” I think you’ve already got this language thing down! :O) Good luck with cutting back on the hours.

I just love this, Colleen! Of course I love all things language, but how fascinating how the studies showed the differences in how orientation causes people to think. Amazing.

And great reframing of writerly events! I love that.

Wonderful post!

Thanks, Susan! I thought that was fascinating too. I want that spatial orientation so I never get lost again! Wonder if I start using north, south…etc. if I could develop it? :O)