by Ann Marie Ackermann

I discovered a historical murder case in a 19th-century forester’s diary here in Germany, where I live.

The forester detailed his role in a murder investigation. The mayor of Bönnigheim was assassinated in 1835 and a letter came from the USA in 1872 offering the solution to the murder.

The forester found the critical corroborating evidence in the forestry archives that allowed the German prosecutor to close the case as solved.

19th-Century Germany’s Oldest Cold Case Ever—Solved in the USA

The uniqueness of this case struck me immediately. I used to practice criminal law in America and knew how difficult it was to solve a cold case before the advent of DNA testing. A 37-year time span is simply unheard of in the 19th century.

Research in the German archives and libraries confirmed my suspicion. This case turned out to be a German record-breaker: 19th-century Germany’s coldest case ever solved and its only case ever solved in the USA.

But when I discovered the connection to Robert E. Lee, I knew I was on to something much bigger and got a book contract with Kent State University Press fairly quickly.

That enabled me to write precisely the kind of book I love to read—one about solving a historical murder in the archives.

Publishing a Book in the Middle of Chemotherapy?

My cancer diagnosis came between finishing the book and the launch.

I was very lucky that my publisher was still able to push the launch date back several months. Otherwise, the book would have been published right in the middle of my chemotherapy! I wouldn’t have been able to do anything to help promote it.

What proved extremely helpful was hiring two independent publicists. Stephanie Barko did a lot of outreach in obtaining book reviews and JKS Communications helped set up an American book tour, which I’ll do in October 2017.

Together with Kent State University Press, they made a great team. My publicists enabled me kick back and focus on my healing. I’m so thankful for their help.

Using Historical Facts to Create a “Plot”

Piecing together archival material to create a narrative arc [was the biggest mental challenge].

Everything in my book is factual and supported with endnotes, but I wanted it to read like a murder mystery. That meant reading a lot of old correspondence, diaries, and investigative files to find building blocks for my “plot.”

What made the plot hard was turning a historical story into a good narrative arc without distorting the facts. That meant reading through a lot of archival material to select material that moved the story line forward.

I chose information that offered a deeper look into a person’s character—for instance, when I read in the archives that a captain was hiding an orthopedic disability from the army, I included that. Facts that increased the tension or that foreshadowed an event were also useful. I added details about a bird species that has gone extinct, or a flock of vultures, to foreshadow a death.

When You’re Healing, It’s Okay if Things Come Out Late

Exhaustion [was the biggest emotional challenge]. Chemotherapy is fatiguing and I had days and weeks that were so tiring I couldn’t do anything.

I learned to listen to my body and take breaks. It was okay if a blog post came out a week late. It was okay if my newsletter wasn’t timely or I couldn’t get back to my publisher right away.

Sometimes napping the day away was more important.

How Writing This Book Enabled Me to Piece Together Two National Mysteries

Without question, [the biggest triumph in writing this book] was the moment I realized that Robert E. Lee had written a letter about the German assassin. Of course, Lee had no idea of the man’s criminal history.

So writing this book enabled me to piece together two national mysteries.

Who was the man Robert E. Lee praised after his first battle, the Siege of Veracruz in the Mexican-American War? And how did Germany solve this case after so many years?

Writing this book gave two of my interests—history and mystery—expression. Research, writing, and networking with readers were also a lot of fun. They allowed me to tap unexplored talents.

My Book Gave Me Focus and Hope While Going Through Cancer Treatment

Indirectly, [writing is a spiritual experience for me]. My book offered a wonderful distraction while I underwent cancer treatment.

While other patients might have groveled in self-pity, I remained focused on the book, which gave me hope. I had something to look forward to. And I’m convinced that hope contributed to the healing process.

At the same time, my cancer offered a counterbalance.

I’ve learned my book is not the most important thing; my health is.

In the end, sales don’t matter. When I start my American book tour in October, I’ll be focused on having fun, not business. And I can thank my cancer for that.

Could It Be That Writer’s Block is a Symptom of Stress and Fatigue?

Whether you have an illness or not, learn to listen to your body. Learn to take breaks. They will rejuvenate you.

Sometimes I think writers should look at writer’s block as a symptom of stress and fatigue. They are for me.

Stepping away from writing and marketing pressures for awhile always helps me.

* * *

Ann Marie Ackermann is a former attorney with focuses on criminal and medical law. Eighteen years ago she moved to Bönnigheim, Germany, the town in which the assassination occurred, and is a member of its historical society.

Ann Marie Ackermann is a former attorney with focuses on criminal and medical law. Eighteen years ago she moved to Bönnigheim, Germany, the town in which the assassination occurred, and is a member of its historical society.

Ackermann’s intimate knowledge of the town and of the German language enabled her to bring the German and American sides of this story together. She has a number of academic publications in law, ornithology, and history.

For more about Ann and her work, please see her website, or connect with her on Facebook and Twitter. (Photo by Inge Hermann.)

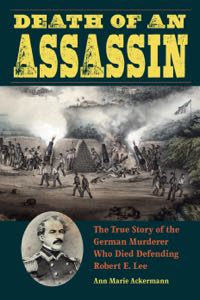

Death of an Assassin: From the depths of German and American archives comes a story one soldier never wanted told. The first volunteer killed defending Robert E. Lee’s position in battle was really a German assassin. After fleeing to the United States to escape prosecution for murder, the assassin enlisted in a German company of the Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Mexican-American War and died defending Lee’s battery at the Siege of Veracruz in 1847. Lee wrote a letter home, praising this unnamed fallen volunteer defender. Military records identify him, but none of the Americans knew about his past life of crime.

Death of an Assassin: From the depths of German and American archives comes a story one soldier never wanted told. The first volunteer killed defending Robert E. Lee’s position in battle was really a German assassin. After fleeing to the United States to escape prosecution for murder, the assassin enlisted in a German company of the Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Mexican-American War and died defending Lee’s battery at the Siege of Veracruz in 1847. Lee wrote a letter home, praising this unnamed fallen volunteer defender. Military records identify him, but none of the Americans knew about his past life of crime.

Before fighting with the Americans, Lee’s defender had assassinated Johann Heinrich Rieber, mayor of Bönnigheim, Germany, in 1835. Rieber’s assassination became 19th-century Germany’s coldest case ever solved by a non–law enforcement professional and the only 19th-century German murder ever solved in the United States. Thirty-seven years later, another suspect in the assassination who had also fled to America found evidence in Washington, D.C., that would clear his own name, and he forwarded it to Germany. The German prosecutor Ernst von Hochstetter corroborated the story and closed the case file in 1872, naming Lee’s defender as Rieber’s murderer.

Relying primarily on German sources, Death of an Assassin tracks the never-before-told story of this German company of Pennsylvania volunteers. It follows both Lee’s and the assassin’s lives until their dramatic encounter in Veracruz and picks up again with the surprising case resolution decades later.

This case also reveals that forensic ballistics―firearm identification through comparison of the striations on a projectile with the rifling in the barrel―is much older than previously thought. History credits Alexandre Laccasagne for inventing forensic ballistics in 1888. But more than 50 years earlier, Eduard Hammer, the magistrate who investigated the Rieber assassination in 1835, used the same technique to eliminate a forester’s rifle as the murder weapon. A firearms technician with state police of Baden-Württemberg tested Hammer’s technique in 2015 and confirmed its efficacy, cementing the argument that Hammer, not Laccasagne, should be considered the father of forensic ballistics.

The roles the volunteer soldier/assassin and Robert E. Lee played at the Siege of Veracruz are part of American history, and the record-breaking, 19th-century cold case is part of German history. For the first time, Death of an Assassin brings the two stories together.

Available at Amazon and wherever books are sold.

Coolest thing I’ve read all day! My WIP is a narrative nonfiction piece based on historical research. Every statement has to be substantiated (or indentified clearly as supposition), so I appreciate your points about maintaining the narrative arc and maintaining tension (not to mention health issues that require rationing of energy). Many thanks for this post.

Jeri — you’re welcome and good luck with your own health and writing issues. It’s interesting to see how your journy led you to the discovery that you’re more suited to non-fiction.

I can so relate to those days when on chemo and napping is the one and only priority a body can seem to muster the time for. I too have found my way back to writing due to my cancer diagnosis. I undertook a GoFundMe campaign to help makes ends meet during treatment since I could only freelance part-time. I knew if I told those who donated to my campaign I would write a post every week for a year about what it’s like to deal with breast cancer, I would meet that deadline no matter what. It’s been therapeutic, yes. But up until getting diagnosed, I’d always waffled about whether to write fiction or narrative nonfiction. I’ve finally realized my voice is best suited to nonfiction. Plus, what I am now posting will eventually become part of a memoir that looks at all the crazy stuff that has happened the past three years of my life. Thank you for sharing your story.