Author Linda Sienkiewicz isn’t new to writing about suicide. But this time, she channeled her love for her son through poetry, and found a new creative outlet for her grief as well as her cherished memories.

by Linda Sienkiewicz

I never sat down with the intention to write poems about my son or his suicide.

In fact, I actively avoided it because the pain was too much to bear.

Then, in 2019, I attended a performance with friends to see a Dutch cellist. One of his songs, Solo Suite, was so sad and haunting that it took me back to the moment when my husband and I had found our son, deceased, in his apartment.

There, at the concert, the start of a poem came to me while I fought tears. When I returned home, I felt compelled to write.

That poem, “Solo Suite,” was later a Finalist for the 2022 Julia Darling Poetry Prize. I continued to write after that, and each time, it got a little bit easier.

I Had to Allow Myself to Walk Away from Writing About Suicide

Doing a deep dive into loss and grief initially took an emotional toll, even nine years after my son’s death.

I had trouble sleeping. I cried easily. I had sad dreams.

Writing didn’t feel cathartic at first. I had to allow myself to walk away from it.

Writing Poems and Writing Fiction: They’re So Different

I studied and wrote poetry for years before I began writing short stories and novels.

Writing poetry is a process of whittling down your message to its barest form. Poetry is economic language. You can’t get away with redundancy or clichés.

To me, the differences between working on poetry and fiction are so different, it’s like painting an abstract and painting a realistic landscape.

It’s true that both poetry and fiction make use of the same tools, such as metaphor, dialogue or narrative, but otherwise, at least in my brain, the process for each doesn’t really overlap.

In that way, I find it easy to switch from writing one to the other.

Going from Writing Poems to Working on Poems

When I began working on writing poetry in the 90s, I read tons of contemporary poets and literary journals. I attended every conference, workshop and retreat that I could manage.

In that way, I went from simply writing poems to working on poems. I took a college course in form poetry. I read books on poetry and wrote every day.

I followed the same approach when I took an interest in fiction writing. You have to study the craft, no matter what type of writing you’re working in.

CLEAN

We return to Ohio to empty your apartment.

Pictures of Marilyn and Sinatra on your walls,

the pre-lit Christmas tree I gave you

two years ago, outside on your patio.

Your fridge, immaculate, save for a magnet

on the door of your young niece

in a pink ballet costume. Your laptop, scrubbed.

Six drained wine bottles on the counter

and we can’t find the key

for the ’81 Corvette we didn’t know you had.

I sprain my back trying to lift

a duffle bag loaded with old magazines.

The autopsy report comes back clean, only

mild arterial buildup. Hereditary.

I Hope My Writing About Suicide May Help Others

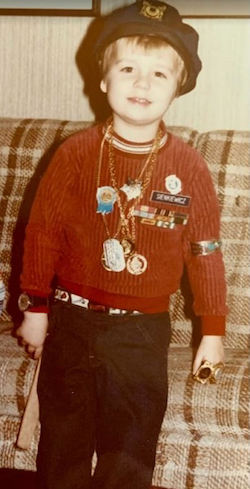

I felt I reached a turning point when I wrote a poem about my son as a little boy raiding my costume jewelry so he could look like Mr. T, how he’d scrap with the neighbor boys, and how we often laughed about when the candles from his cake caught my sweater on fire on his twelfth birthday.

It was the first poem about my son—who he really was. It was then that the chapbook transitioned into a way of honoring him and his life.

I even included a poem of his.

Some of the poems in Sleepwalker are previously published, but they fit the narrative since they were about Derek or our family.

Then, when I began to put the poems together, I realized the book could be helpful to others who have suffered the loss of a loved one to suicide. I included links to suicide prevention sites and supportive resources.

Writing About Suicide: You Have to Address the Feelings of Guilt

It was important to address the overwhelming guilt a parent feels when they lose a child to suicide.

I mean, it’s inevitable, and I suspect it happens with anyone who’s lost someone to suicide.

It’s natural to ask “what if….” but getting wrapped up in blame can keep you running in circles. We have to accept ourselves as flawed beings. And, as humans, we can only do so much.

As a Parent, You Must Deal with the Stigma

Suicide is difficult because of the stigma.

People ask “How did this happen?” or “Weren’t there signs?” and then you begin to wonder, did I do everything I could have to prevent this?

Unfortunately you’ll never know.

We had taken our son to the hospital before, and we were about to do it again, but we were about 12 hours too late.

He might have gotten better, but then who’s to say he wouldn’t have stopped taking medication again? You can’t force an adult to take antidepressants. You can’t force them into therapy.

That aspect breaks my heart.

When Coping with a Loved One’s Suicide, It’s Important to Share Good Memories

I found solace in the small cemetery in my neighborhood. When I read the gravestones of babies, children and young adults who are buried next to their parents, I realized I was not alone in my grief.

Illness, accidents and suicide take lives of loved ones every single day. It’s not fair, but it is reality. Life is fragile.

It won’t always hurt. One day you will be able to talk about your loved one and the loss without crying. You will feel joy and happiness again, and you will accept that it’s all right to feel joy and happiness.

We honor our son in little ways. On his birthday, we get pepperoni pizza because it was his favorite. Every Christmas, we decorate a small tree with the ornaments I collected for him since he was a baby. We keep his picture out. We talk about him, “Oh, Derek would have loved this,” or “Remember the first time we took him to the beach?”

It’s important to share good memories.

Advice for Other Writers Writing About Suicide

Don’t push yourself. My son died in 2011. It wasn’t until three years late that I wrote an essay about the black hill spruce tree we got for our first Christmas without him.

I didn’t write the first poem about his death until 2019. And even then, I didn’t have an inkling that I’d put together a collection of poems about him.

Read more about Linda’s fiction on her previous Writing and Wellness post.

* * *

Linda K. Sienkiewicz’s work has been published in numerous literary journals and anthologies. Her debut novel earned multiple finalist awards.

Linda K. Sienkiewicz’s work has been published in numerous literary journals and anthologies. Her debut novel earned multiple finalist awards.

She also has a poetry chapbook award from Heartlands Today. She wrote and illustrated a picture book titled Gordy and the Ghost Crab.

Her fifth poetry chapbook, Sleepwalker, is forthcoming from Finishing Line Press. Linda holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine. For more information about her and her work, please see her website and follow here on Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Facebook.

Sleepwalker: Linda K. Sienkiewicz’s poems speak with intense fierceness to hard-earned compassion and painful healing after her eldest son’s suicide.

Sleepwalker: Linda K. Sienkiewicz’s poems speak with intense fierceness to hard-earned compassion and painful healing after her eldest son’s suicide.

Trying to make sense of tragedy, she unearths the heartbreak of motherhood and loss, revealing tender, resilient love in poems that embrace who her son was and what he will never be.

Those who have suffered such a loss will know they are not alone.

Available from Finishing Line Press.

Linda, I am so, so sorry for your loss. I’ve commented/quote tweeted with you before today. Your writing about your son always makes me cry. My son’s best friend committed suicide. It’s a grief, a hole in the heart, that really never heals. Thank you for sharing in this post. I will read Sleepwalker.

I’m honored to be featured here, Colleen. Thanks for the space to share an important message.

Thank you, Linda! Great to have your thoughts here again, and congratulations on the book of poetry. :O)