At this time of year, I always find myself slipping into a period of reflection.

How has the year gone? Where am I, in terms of my professional and personal growth? How did I do on my goals?

Underneath all of this is perhaps the biggest question on my mind, and maybe on the minds of other writers, as well.

Did I become a better writer this year?

We all have our own ways of evaluating our progress, but at the same time, it’s difficult to be objective when it comes to our own stuff. We may think we’re really improving, but how do we know for sure?

Humans (Writers Included!) Tend to Overestimate Their Abilities

In 1999, researchers published a landmark study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that showed humans have a knack for overestimating their own abilities.

“People tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains,” the authors wrote, explaining that over the course of four different test periods, participants that scored in the bottom quartile on humor, grammar, and logic “grossly overestimated their test performance and ability,” estimating themselves to be in the 62nd percentile when they were actually in the 12th.

As writers, we can be equally guilty of overestimating what we put on the page. In a way, that’s good, as we need that confidence to survive what is often a long and arduous career in the arts. On the other hand, though, it can keep us from improving as quickly or as efficiently as we might.

According to the study, “when people are incompetent in the strategies they adopt to achieve success and satisfaction, they suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it.”

What if we “think” we’re improving, but we’re actually getting no better at all? What if this time next year, our writing has not advanced, and we are no closer to our goals of publishing (or selling or of becoming bestsellers or whatever our dreams are), than we are right now?

I find this to be a disturbing thought, so when December rolls around, I want to evaluate my progress in a way that goes beyond my own subjective opinions. How can we tell how much (or how little) we’ve actually improved?

We Tend to Inflate Our Own Egos

To look at our own weaknesses isn’t fun. Most of us avoid it.

“The desire to feel special is understandable,” writes Kristin Neff, Ph.D. and associate professor in human development and culture at the University of Texas, Austin. “The problem is that by definition it’s impossible for everyone to be above average at the same time.”

We can inflate our own egos and state that absolutely, we are much better writers now than we were this time last year, but as Neff says, “this strategy comes at a price—it holds us back from reaching our full potential in life.”

So how do we get past this natural human tendency and see ourselves as objectively as possible?

I have a few ideas. Let me know what you think. If you have other thoughts, please add them to the comment section below!

A Word About Critiques

We tend to think the only we can get a legitimate evaluation of our own writing is to ask someone else. I caution you to realize it’s not that simple. As I mentioned in a previous post about writing critiques, they are subjective, and many people are simply not good judges.

Though asking for feedback can be a good place to start, make sure you’re keeping the following points in mind to avoid a critique fall-out.

- Always get more than one: Three is best. Then you can compare. Pay particular attention to the things that come up across the board—they are likely the areas where you need to improve. If something is mentioned only once by only one reviewer, use your best judgment to determine whether it’s worth paying attention to.

- Consider the source: Who’s doing the critique? A friend or family member? Another writer? A professor? A book doctor? A member of a writing group? An agent? Always consider the source when reviewing the feedback, and the possible motivations behind what the person says. As Steven Pressfield noted in his great blog on the topic: “It’s been my experience that very, very few people can read something and tell you accurately what’s wrong with it,” he writes. “And practically nobody can tell you how to fix it.”

- Notice how you feel: You can use your feelings as an indicator of what feedback is good feedback. Listen to the quiet little voice in the back of your head—the one that also speaks up when you reach for one too many cookies after dinner. The smart one. When it encounters a statement it knows to be true, it will tell you. Usually these are the comments you have an emotional reaction to. “My dialogue? My dialogue is great!” If you feel like scratching out the notes with a Sharpie, wait until you calm down, and review the comment again. Most likely you’ll find some truth in it. The other comments? Let them slide off your back.

7 Ways to Evaluate Your Progress

Now that we’ve got critiques out of the way, let’s look at some other ways you might evaluate your progress toward becoming a better writer this year.

1. Time Spent On Your Craft

Not talking marketing here, or social media efforts, or “thinking” about writing. How much time did you actually spend writing? As a music teacher for over 25 years, I know that time spent practicing equals improvement, in every case, no exception. The more you do it, the better you get at it.

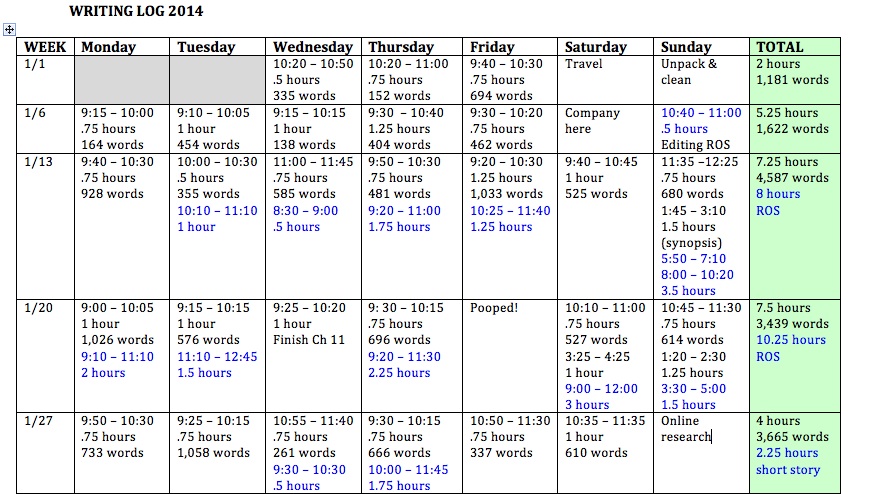

How can you tell? I keep a writing log. I built it in Excel, and it looks something like this:

Note that I put in black only the time spent actually writing something new, and the accompanying word count. This log is strictly for my own projects, and doesn’t include time on this blog or time spent writing for my freelance clients. The hours in blue mark the time spent editing—in this case, edits on my first novel (coming out Spring, 2015).

Note that I put in black only the time spent actually writing something new, and the accompanying word count. This log is strictly for my own projects, and doesn’t include time on this blog or time spent writing for my freelance clients. The hours in blue mark the time spent editing—in this case, edits on my first novel (coming out Spring, 2015).

After New Year’s, I can total up the time I spent on writing for the entire year, and compare that with totals from years past. I’ve been keeping a log since 2011, and can proudly say I’ve put in more total hours every successive year. (Here’s hoping 2014 is no exception!)

You may think that time spent with butt in chair doesn’t really equate to “better” writing, but I would disagree. It’s the only way to better writing, and a concrete way to evaluate your progress every year.

2. Outside Feedback

I’m not talking just critiques, here, but how your writing performed in the real world. Ask yourself these questions—your answers give you clues to your progress.

- Did you submit? Contests, agents, editors—did you submit? How many times? (I recommend keeping track in a document similar to the writing log above, only with columns for each submission, the date of the submission, and the results or response).

- What were the results? Did you finalize or place in a contest? Did an editor or agent comment on your submission? Did an editor or agent request the full manuscript? Did you have a story published? Did you get a book publishing contract?

- How did you respond? If your submission came back, how did you respond? Did you send them back out? Did you work on the piece and resubmit? Or did you give up?

- What was the total? Did your total number of submissions outpace those you sent out last year?

3. Your Own Education

If you wanted to be a pilot, you’d invest in flying school. If you wanted to learn how to sculpt, you’d take a sculpting class or invest in lessons with a private teacher.

Did you take similar steps to further educate yourself as a writer? All of the following can contribute to your learning—which leads to better writing. How many of these did you engage in this year?

- Writer’s conferences

- Writing classes and/or workshops

- Craft books

- Online courses

- Work with a writing teacher you trust

- Reading books in your genre and actually evaluating how they were successful

- Performing writing exercises and evaluating the results

4. Focused Practice

The hardest thing for my music students to learn is focused practice. Here’s what happens:

Let’s say Johnny is working on a solo. He plays it from the beginning down to the fourth line. There, he encounters a passage that he hasn’t mastered. He makes a mistake on it, stops, and….

goes back to the beginning.

The problem, of course, is that by going back to the beginning, he avoids the problem spot and plays what he already knows—again. When he re-encounters the dreaded passage, he messes up and then goes on, or returns to the beginning.

What needs to happen instead? Focused practice on the problem passage.

Thing is, that’s the hard part, and most students don’t want to slow down and pick through the hard part. It’s not nearly as much fun as playing the part they already know.

The result is they continue to become familiar with the part of the piece they can already play, while avoiding the hardest part. And that’s the part they need to learn to become better musicians.

As writers, we can make the same mistake by coming up against something that challenges us—and then avoiding it.

Let’s take plot, for example. Early in my writing career, I struggled with it. Many other parts of writing came naturally to me, but the rise and fall of scenes and the overall plot structure was something I didn’t know much about. I bought books, read a zillion online posts, took classes, worked with an editor, and sketched out the plots in my novels. It was like homework, but I knew I had to do it to get to the next level.

I didn’t become an outliner. (I’m still a “pantser” to this day.) But the idea of plot sunk into my brain (I hope!) so that today, I’m much more conscious of it as I’m working, and particularly when I’m revising.

My students have accomplished the same by slowing down and rehearsing the hard passages (usually in the lesson with me!). Some gain the self-discipline to do it themselves, a skill that translates into many other areas of their lives.

But it’s not easy. It never is. Much more fun to play (or write) the parts you know!

Did you practice the hard stuff this year? Did you work on dialogue, setting, characterization, plot—whatever part of your writing is weakest? Did you push yourself to slow down and really examine your writing and compare it to the masters to see how you can improve?

I took a workshop with Dean Wesley Smith and Kristine Kathryn Rusch in 2010 (highly recommended). Kristine said that in each new manuscript she and Dean write—and they’ve written hundreds of novels between them—they work on something new. This novel? Setting. Next one? Characterization. Each time, they focus on improving something.

How about you?

5. Your Own Comparison

This is really easy, and really fun.

Simply take out a recent piece of writing, along with a similar piece you completed last year. (Make sure there are at least 12 months between the completion of the two, and that you haven’t read either for at least a month.)

Then sit down, and as objectively as you can, read. Read as if you are reading someone else’s work. Make notes if you like.

What do you see? Which piece of writing is better? What conclusions can you draw from the experience?

“While it may be painful to go back a few years,” writes freelance writer Alica Rades, “it can also be a good thing, giving you a chance to realize what you have already improved on and help you determine how you can improve even further with your writing skills. Use these past pieces to determine where you’ve been so that you can get a better idea of where you’re going.”

6. Compare with the Masters

I have a lot of friends by my writing chair.

Dennis Lehane. Andre Dubus III. Thomas Williams. Margaret Atwood. Even Terry Goodkind.

Whenever I get stuck in my writing, I grab one of them up. I read. I evaluate. I compare.

Wow. Look how he did that. How can I do something similar?

Here’s a fun way to evaluate your progress. Type out a passage from a favorite book. Choose a passage that’s similar to one of yours. If you have two people arguing in your story, for example, find a similar passage in one of your hero’s stories. If you have a physical fight in your story, find a similar fight in one of your hero’s stories. Type it out. Compare the two. What do you see? Where could you improve?

7. How Do You Feel?

Be careful with this one. You can fall into the over-estimating trap the researchers talked about.

Ask your ego to stay out of the room, and ask yourself: Did I become a better writer this year?

Be compassionate with yourself. Maybe you suffered a major upheaval this year in your life—a death in the family, a job change, a move, an illness. Maybe you launched a first book and were so overwhelmed with marketing you lost time on your craft. Maybe the stars just didn’t line up right for you to make real progress this year.

Or maybe you achieved everything you wanted to, and your career is taking off.

Either way, try to be objective, not critical.

“I slowly came to realize that self-criticism—despite being socially sanctioned—was not at all helpful, and in fact only made things worse,” writes Neff. “I wasn’t making myself a better person by beating myself up all the time. Instead, I was causing myself to feel inadequate and insecure, then taking out my frustration on the people closest to me. More than that, I wasn’t owning up to many things because I was so afraid of the self-hate that would follow if I admitted the truth.”

This is the key to facing the truth about your own progress (or lack of it)—self-compassion. Be kind to yourself. No criticism here, just an honest evaluation. That way, you’ll be more likely to accurately assess your current skills as a writer.

Once you’ve figured out where you are, what’s next?

Setting goals for next year, of course!

More on that in the next post. (grin)

Happy holidays, everyone!

How do you evaluate your progress as a writer? Please share your tips with our readers.

Sources:

Justin Kruger and David Dunning, “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1999; 77(6): 121-1134, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.64.2655&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Kristin Neff, “Why Self-Compassion Trumps Self-Esteem,” The Greater Good Science Center, University of California, Berkeley, May 27, 2011, http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/try_selfcompassion.

I heard about that study on people overestimating their abilities too, and it totally depressed me! I already feel like I’m not doing well at a lot of things, so given that study, how bad must I really be?? I was one of those hyper-grade-focused kids in school, and have often wished as an adult that a teacher would follow me around and grade me on life so I would have an objective opinion on how I was actually doing. Your techniques are much more useful! I have always relied totally on critiques, under the assumption that my own opinion can’t be trusted. But these are some great tools to make sure I’m being somewhat objective when I do judge my own work!

Oh no! Well I don’t know if it applied to you, Chere! It was the people who thought they were doing really well that were off in the study. But I hear you–I was the same way, looking for that outside feedback. As writers we really have to figure it out on our own, though. Hope the tips are helpful!

I HAVE to be better than last year since I wasn’t writing then, but even going back a few months and rereading some things can be painful! I appreciate the tips.

No place but up from ground zero, right? :O) Yes, I hear you on the painful–and it sounded so good back then, right? Thanks for your input, Anita. So appreciated!

Thanks for this, Colleen, I found it really thought-provoking and will definitely be following some of your tips over the Christmas holiday. I always find it incredibly difficult to keep a handle on what my own writing looks like from an objective point of view, but it’s so important to try and do that. Thank you, and have a wonderful holiday! x

Thanks for the feedback, Elizabeth! I hope it will be helpful. I’m definitely open to other ideas as well. I think it’s so difficult to evaluate one’s own work, but I do find that these things have helped me improve. Happy holidays to you and your family as well!