I was 11 when the first version of These Lies That Live Between Us came to me.

At the time, I lived in Japan, and one of my pastimes was to “write songs”—by which I mean I’d take the silly little love songs on my CDs and write my own silly little love song lyrics to go to the tune.

There was this band, “Garnet Crow,” that I loved. I’d heard that for any given song, their singer would write the melody, one keyboardist would write lyrics, and the other keyboardist would compose the arrangement. I played the piano and loved writing, so I was probably trying to emulate the lyricist-keyboardist. Eventually, it started bothering me that I was simply recycling other people’s music. I thought that I should write something totally original.

I Admitted to Myself: This Would Have to Be a Book

I Admitted to Myself: This Would Have to Be a Book

It was a lot harder. I was used to having original lyrics for any given song that I could look to for inspiration, so I wasn’t used to starting from scratch. After a few failed attempts at a melody, I decided to write lyrics first. I knew how to write stories, so my lyrics were more story than song.

It was a short little story about the Princess of Hearts running away from home because she couldn’t deal with the pressures of royal life. I wrote a melody to go with it, and was pretty happy with myself. But I wanted to know what happened next, so I wrote another song. In that song, she met a dashing knight, who was secretly the Prince of Spades in disguise. In the next song, the Princess of Hearts became a maid in the court of Diamonds. This kept going until I gave up the pretense that these were songs at all; I admitted to myself that this would have to be a book.

I’d Forgotten My Other Characters Were People, Too

I’d Forgotten My Other Characters Were People, Too

I wrote all these song lyrics in Japanese, but I had this mental state where I had to write stories in English. The first time I tried to translate these songs into an English story, it felt all wrong. It took a few years for me to comfortably adapt the voice.

I spent these years planning my story: I gave all the characters names, and drew up family trees, maps of the countries, floor plans of all the relevant buildings, social relationship charts… When I was maybe about 15, I had most of the story written up in some form.

I was almost done, writing the scene when the Nicki (formerly the Princess of Hearts) came home from her adventure—and she and I discovered as one that her little sisters hated her. I do mean hated. I was shocked. My clever, resourceful, brilliant Nicki, who loved her sisters more than anything and never would have hurt them, was shocked, too—and this broke her.

I stopped writing for some time out of shock. Eventually, I was forced to admit to myself: I’d overlooked how her sisters would feel about anything Nicki was doing. Nicki never would have made that mistake. I’d been too busy living vicariously through Nicki to see it. I realized that I’d forgotten that the little sisters were people, too.

I rewound. I decided to give each sister a personality and a story. Obviously, Nicki would never leave a burden she hated to her sisters, so it should be the elder of the younger two, Andrea, who runs away. I figured that Courtney would need a story too, but wasn’t too worried about that yet. Being a teen, I based these characters on my own sisters. I outlined Andrea’s story—and immediately hit a roadblock. I couldn’t understand it. I knew my sisters’ personalities, and I had my outline. What more did I need?

It Took Me Some Time to Realize I Couldn’t Write a Character Based on a Real Person

It Took Me Some Time to Realize I Couldn’t Write a Character Based on a Real Person

It took me an embarrassing amount of time to realize that I couldn’t write a character based on a real person. I was spending too much time trying to figure out what my sister would do—an impossible endeavor—rather than simply asking what the character would do.

I was in my late teens before I realized this. I scrapped and redid my character designs. Andrea and Courtney were scratched out and replaced by Estelle and Gwenaëlle. I wrote a few vignettes about these new girls, just to reinforce to myself that these girls are not my sisters. During all of this, while I was focusing on the other two, Nicki—once my Mary Sue self-insert character—grew out of me and became something all her own. No longer was she the reluctant princess; she was the Heir, and she relished it.

So, why did I pursue this story? Because it’s been living and growing and breathing with me, haunting me for over fifteen years. I’m not sure I could have abandoned it if I’d tried. I only hope I did it justice.

First and Foremost I Want a Reader to be Able to Follow and Enjoy the Story

One of the last challenges of writing the book, and one that I’m still not fully satisfied with, is the beginning. Some people seem to like it, which is wonderful; but other people tell me they have trouble with the beginning, to which I can only feel apologetic. I know who Gwen is so well now, after all these years, and her relationships with Nicki and Stelle, that it was extremely difficult to try to figure out how to convey what needed to be conveyed to the reader.

There’s a similar issue with the characters who periodically change name over the course of the story. Though I’ve done a lot to make this clearer compared to earlier drafts, I still get readers who are confused by the name changes. It’s frustrating, because obviously first and foremost I want a reader to be able to follow and enjoy the story. On the other hand, the name changes are thematic to me, and the relationships between these characters and their names is something I see as emblematic of who they are.

I still wonder if maybe this was me holding onto the wrong thing—maybe I ought to have stuck with 1 name per character throughout, with maybe 1 exception. Even though I went as far as indie publishing to avoid having to change this, I’m still not completely certain, if I’m being honest. I just know that this was the way I felt compelled to tell this story.

Mom’s Dying…What If She Never Reads It?

Mom’s Dying…What If She Never Reads It?

As my mother was dying, she offered to proofread this book. It wasn’t finished yet, at the time. I’d finished a version that focused more on Stelle in 2011. As soon as I read my finished manuscript from start to finish, I knew that I didn’t like it. The first third was basically all episodic adventure with nothing plot-related happening until the end, the second third was very heavy on exposition, and then the last third was suddenly a dizzying amount of action and plot. To put this in perspective, Alderic’s entire storyline from These Lies is one sixth of that story: the first half of the last third.

It was easy to figure out how to fix this in my mental outline: instead of each sister getting a book, I would cut most of the first two-thirds of that book, expand the last third into a full novel, and entwine Gwen’s story with Stelle’s. It made sense. They intersected at the climax, which was always going to be a little jarring from either side when they were two separate stories. I wrote a draft of this version and was in the process of editing it when my mother got sick.

When she offered to read it, I did so want her to. But she had very little energy, and I wanted to make sure she only read the best I had to offer. I knew that there were deep, deep flaws with my manuscript. I wanted to fix them, before showing it to her.

I couldn’t write or edit or anything. At all. I’d sit down in front of my manuscript and I’d start to panic—Mom’s dying, I have to finish, what if she never reads it?—and I’d have to stop because I was having an anxiety attack, or suddenly needed to go to bed and lie there for the rest of the day.

And so the source of my anxiety is exactly how it played out. She died without reading a single page.

It Would Be Easy to See It as a Failure, and then I’d Never Write Another Word Again

It Would Be Easy to See It as a Failure, and then I’d Never Write Another Word Again

The thing was, a few months—by which I mean four or five months—after she died, after most things had been squared away, the depression started lifting and I could write again. At first, it was stop-and-go. Then it grew easier and easier and easier, until I was rewriting entire chapters and my beta-readers were remarking on the ease of the new chapters compared to the old ones.

I don’t know if this counts as getting past the issue. I could see this as my failure, if I so chose. It would be easy to see it as a failure, I think, and then I’d never write another word ever again. But I don’t. I can still write my stories, and it somehow, in some way, all came out okay. My story is infinitely better because I rewrote so much of it after going through that.

In the immediate aftermath, when I first started writing again, my grief got channeled into Gwen, and this made Gwen a very different person from the person that she started out. Later, I reached the point where I could acknowledge that the grieving process is no fun for most people to read, and was able to go through and cut most of it out. It still informs Gwen’s character—she’s still going through every bit of that long and excruciating grieving process, as far as I’m concerned. But my readers don’t have to wade through every step of it with her anymore.

I did dedicate the book to my mother’s memory. It’s the best I can do, so it has to be enough. I nearly wrote a whole poem for the dedication, but again, decided that if I’d decided my readers didn’t have to read the brunt of Gwen’s grief, then they certainly shouldn’t have to read any of mine.

The Only Reason I Was Resisting Was My Ego

The Only Reason I Was Resisting Was My Ego

In the very first version of this story, the song that I wrote at age 11, the Princess of Hearts met a knight, who was the Prince of Spades in disguise. When I was getting back into the swing of editing in 2016, most of the story had changed. However, I had this one character, Alderic, who was the prince of Amberria, became a ward to the Ceryllan king to cement an alliance, and then got sent to Ynga as a spy.

If you’re thinking, Wait, why would a spy mission be assigned to someone so valuable? You’re exactly right. It made no sense, except that Alderic was, in some ways, based on the Prince of Spades, who had always been a prince in my mind. It’s the same reason Nicki, Gwen and Stelle are all princesses: they were in the original, and that was one element I never changed.

I knew this was a stretch. So, what did I do? I drew this elaborate diagram explaining everybody’s motivations that made this make sense, and tried to work these explanations into the text. To say it was complicated would be a gross understatement.

I reminded myself of Occam’s razor, and asked myself: What would be the simplest explanation?

That Alderic is not a prince, obviously.

But how would that even work? There would still have to be an Amberrian prince in Ceryll. Alderic would still have to be foreign. Alderic would still have to have a close relationship with Gwen and Nicki.

Then, my mind whispered, Why not split Alderic into two characters: the Amberrian prince who isn’t terribly politically minded and easy for Nicki to manipulate, and his guard who has developed an unlikely friendship with the Ceryllan princesses?

I resisted for about a week. I complained to a friend about it. I tried again to turn my complicated diagram into comprehensible text. I blogged about it—and in the course of writing that blog post, concluded that the only reason I was resisting was my ego.

I yielded, resigning myself to another lengthy edit to make this make sense.

And…I only had to change two lines.

This was before I’d added Nicki’s storyline to the book, so the only storylines were Gwen’s and Alderic’s. Not only were there only two lines to change; suddenly, so many other parts of the story that had seemed iffy before made sense. The other guards’ condescension toward Alderic. His inexperience with politics. That he never met Stelle. It was as though I’d already written Alderic to be the bastard-born outcast of a guard.

It made me realize that I truly only have to learn to trust myself. The stories are all in my head, fully formed and ready to breathe. If I let my ego get in the way, I only hold them back. It was the greatest confidence booster I’ve ever had.

In Learning to Love My Characters, I Learned to Love Myself

In Learning to Love My Characters, I Learned to Love Myself

Writing this book helped me become a stronger, more balanced person.

I suffer from chronic depression. This has been an issue since my early teens, though it took me a decade to put a name to it, and a few more years after that to really admit and face it. I used to repress strong emotions as a habit—not just negative ones, but anything strong—and my therapist remarked that this was likely contributing to my depression.

To finish this book, I had to experience a wide range of emotions and mentalities, to some extent: Stelle’s anger, Gwen’s grief, Alderic’s naïveté, and Nicki’s cunning are just the highlights. Somehow, in letting go and learning to love each of these characters not despite their flaws but with them, I learned to love those parts of myself, too.

In a way, over the course of writing this book, I came to know myself better, and to love all these different facets of myself. In embracing these characters with their flaws, I can let them live out their mistakes, and learn from them, too.

Writing Has Become the Act that Grounds Me

[Would you say that writing is a spiritual practice for you?]

I wouldn’t have used the word “spiritual” unprompted; but having said that, yes.

I’ve come to realize that the stories are there in my mind; I just have to fish them out without letting my ego get in the way. I usually liken this to puzzle solving, but it is very much like meditation, or perhaps prayer. Trying to find an answer inside myself that I know is there, I just have to separate it out from what I think I want just because that’s how I envisioned it or planned it.

Writing has become an act that grounds me, helps me grow and change for the better—while also often distancing me from the real world around me as I sink into my mind.

Advice for a Young Writer: Trust Yourself

Trust yourself. Don’t think about how you should write or shouldn’t write. Just write the way that feels right to you.

Maybe it won’t be ready to see the light of day the first time, or the second or the tenth or the hundredth. But with each iteration, you can learn something that makes you and your writing that much better going forward.

* * *

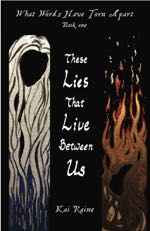

Kai Raine is a writer and cognitive scientist who believes in the power of stories to help readers and writers alike to think outside the box and see past assumptions. Kai reads and writes to experience lives and opinions and possibilities beyond her own. She has lived a relatively nomadic life, being born in the US, then growing up mostly in Japan, and spending most of her early adult life in Europe. She has a BA from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and MScs from the University of Trento and the University of Osnabrück. Kai is the author of the fantasy novel These Lies That Live Between Us.

For more information on Kai and her work, please see her website, or connect with her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or YouTube.

These Lies That Live Between Us: “Good-bye, and good riddance,” were the last words that Gwen’s twin ever said to her.

These Lies That Live Between Us: “Good-bye, and good riddance,” were the last words that Gwen’s twin ever said to her.

But there is no time to grieve. An enemy army has revived a forbidden magic. They’ve invaded a neighboring country, and Gwen’s kingdom will be next. Her only hope of salvation is a legend, so she sets out to find it.

The magic has many names, and many believe they know what it is—but Gwen begins to see that most are mistaken. At last it is the wind itself that forces her to make a choice: accept the forbidden magic and learn it, or die.

Unbeknownst to Gwen, her departure in the night sets a chain of events into motion back home, where her dwindling family turns against one another. As the royal family reveals its internal divide, the opposing factions pounce.

These Lies That Live Between Us is the start of a fantasy epic about family, adventure, love, loss and the ever-changing interpretation of history long gone.

Available at Amazon, Kobo, and Barnes & Noble.

What an amazing journey. You recognized truths in writing at such a young age, and with so many roadblocks. Thank you for sharing.